Located along the eastern shore of Lake Erie at the western terminus of the former Erie Canal, Buffalo is one of several American Rust Belt cities that has seen its fortunes shift dramatically over the course of the last two centuries. Buffalo's most recent decline, in the wake of the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1959, has begun to reverse course. The long hollowed-out city centre is once again showing signs of new life, and the redevelopment of several key areas in and around downtown, including most notably the ongoing revitalization efforts underway at the Canalside District, feature a resurrection of light rail as the backbone of all future development. Once home to a an extensive electrified streetcar network that boasted more than 350 kilometres of track, and supported in its heyday by an additional several hundred kilometres of electrified interurban commuter rail, the City of Buffalo was at one time a major hub, a status that it has not enjoyed for the bulk of the last three quarters of a century. However, as the city's fortunes change, so has that of local light rail, with the brief renaissance enjoyed during the 1980s now blossoming into a full scale resurgence. This edition of Once Upon a Tram will take a look back at the fascinating 180-year history of Buffalo's resilient streetcar network.

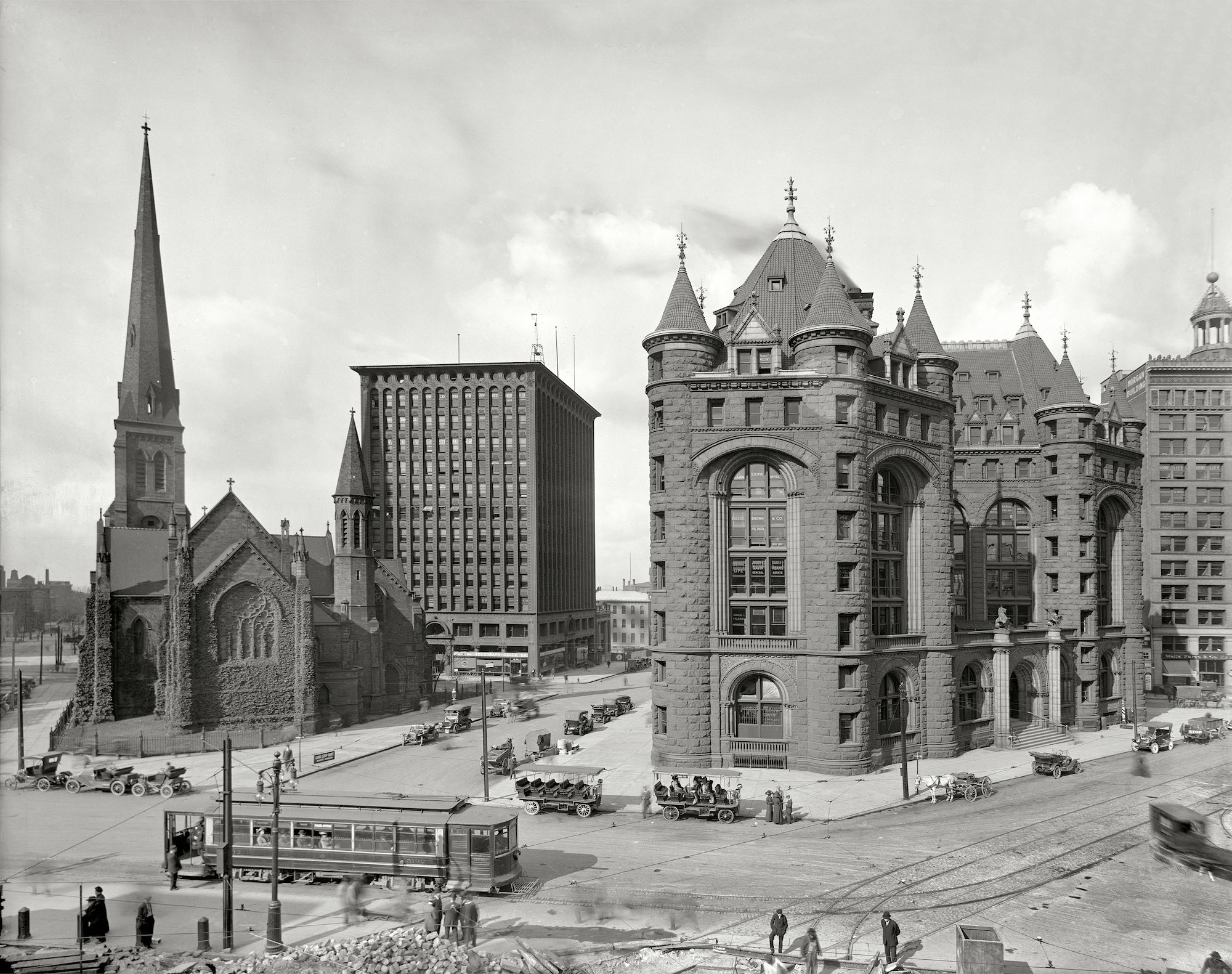

Main Street, Buffalo, N.Y., c. 1900, public domain archival image

Main Street, Buffalo, N.Y., c. 1900, public domain archival image

Beginning in 1834 and predating many North American systems by several decades, Buffalo's streetcar history began with a single horse-car line running north-south through the heart of the city. While service remained limited throughout the early years, the floodgates were opened in 1860 with the creation of the Buffalo Street Railroad Company. A series of private street rail companies jumped into the game over the next 40 years, each of them in turn laying tracks across the growing city, eventually linking Buffalo to Niagara Falls and other destinations as far away as Rochester, creating a network of electrified interurban rail across Western New York State.

Buffalo Street R.R. Co., horse-car en route to the Insane Asylum, c. 1880, image via the Buffalo & Erie County Historical Society

Buffalo Street R.R. Co., horse-car en route to the Insane Asylum, c. 1880, image via the Buffalo & Erie County Historical Society

By the late 1880s, electrification began to make headway into the hodgepodge of private networks then still in operation across the city, and the last horse-cars disappeared from city streets completely by the end of the century. After a series of mergers in the 1890s, the total consolidation of Buffalo's street rail and interurban companies was completed in 1902. At this point the Buffalo Street Railroad Company, the largest at the time, along with all remaining private local and interurban operators came under the control of the newly formed International Railway Company.

Electric streetcars in operation at Lafayette Square, c. 1890s, public domain archival image

Electric streetcars in operation at Lafayette Square, c. 1890s, public domain archival image

Into the early 20th century, Buffalo's consolidated streetcar and interurban network continued to expand, with new lines appearing along seemingly every major corridor throughout the city. Buffalo's original streetcar suburbs owe their existence to the popularity of the system, which recorded a peak 190 million rides in 1919. Well-situated and well-connected, Buffalo's fortunes continued to rise up until WWII, as the city's enviable position at the western terminus of the Erie Canal (which had been a boon to Buffalo's development since its opening in 1820), maintained the city as a major industrial centre and transportation hub.

Continuous row of streetcars moving along Main Street, c. 1896, public domain archival image

Continuous row of streetcars moving along Main Street, c. 1896, public domain archival image

By 1920, Buffalo had more than 350 kilometres of streetcar track, and its citizens were able to access virtually any corner of the city on a single fare. The network's 27 routes radiated outwards from downtown, reaching as far as the city boundaries, north to Kenwood and the Parkside Zoo, west to Emerson and Shiller Park, and south to South Park and the Buffalo and Erie County Botanical Gardens which had gained fame as a popular side attraction to the 1901 Pan-American Exposition.

Streetcars in mixed traffic at Shelton Square, c. 1908, public domain archival image

Streetcars in mixed traffic at Shelton Square, c. 1908, public domain archival image

Despite the runaway success of the Buffalo streetcar network during the International Railway Company's heyday from the turn of the century up to the 1930s, the demands of a growing city and the increasing number of motorists who clogged Buffalo city streets, culminated in a public call for a move to buses, which were viewed as the way forward for the future of the city.

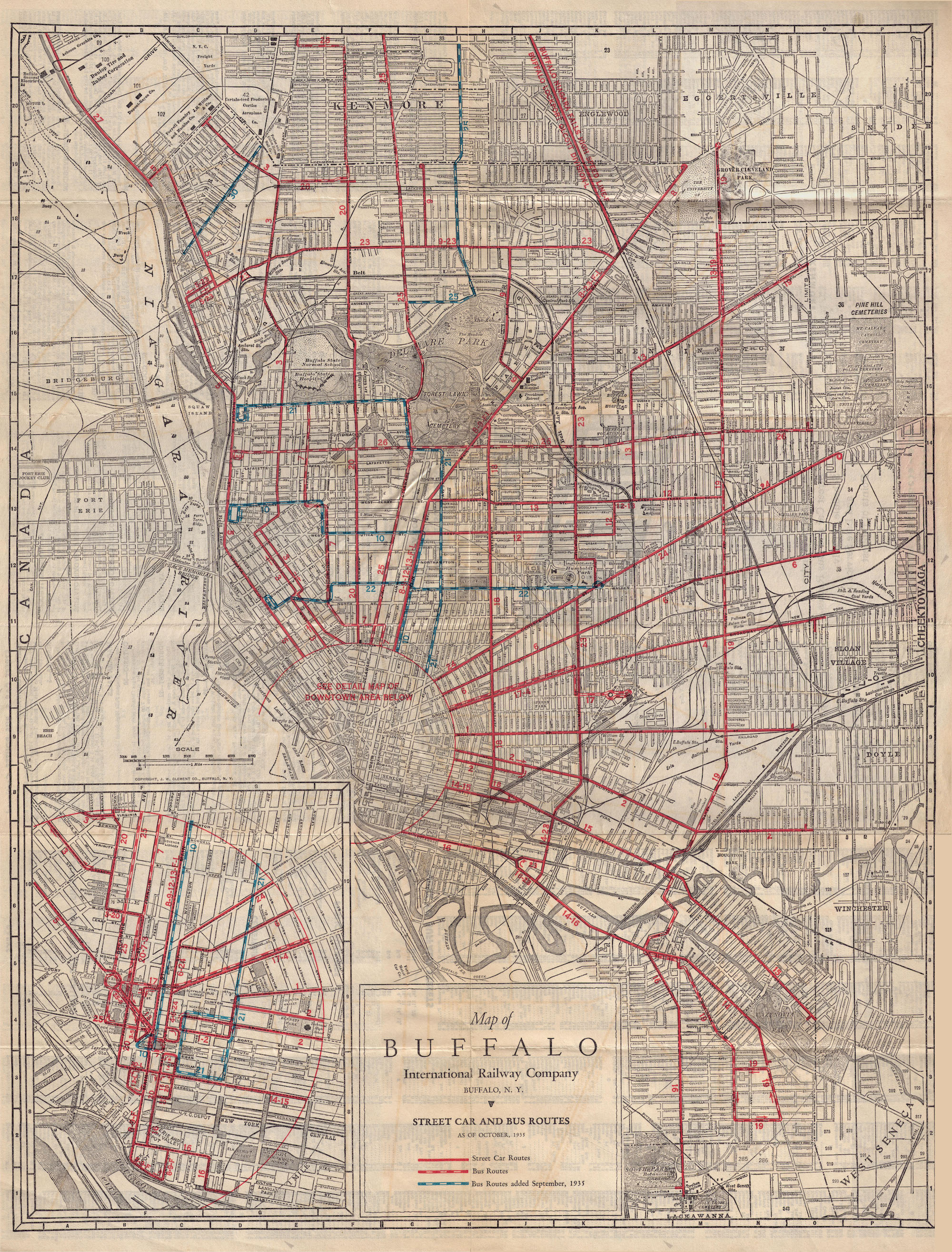

Buffalo Streetcar and Bus Guide, 1935, public domain archival image

Buffalo Streetcar and Bus Guide, 1935, public domain archival image

Published in 1935, the system map above captures the network at the approximate zenith of the streetcar era. The encroachment of new bus lines, shown in blue, signaled the beginning of the end, as the 1940s witnessed the gradual transition and decommissioning of Buffalo's streetcar fleet, a process that was finalized by 1950.

Riding the streetcar, c. 1930, public domain archival image

Riding the streetcar, c. 1930, public domain archival image

Phased out line by line throughout the 1940s, with a six year pause implemented during WWII, the demise of the Buffalo streetcar was slow. Its decline eventually picked up speed in the years leading up to the celebrated Last Run, which took place on July 1, 1950. Like so many similar events in cities across the nation at this time, it was attended by thousands of cheering fans, as the public was persuaded that the era of the trolley had come to an end.

"The Last Ride," Broadway at Mills Street, July 1, 1950, public domain archival image

"The Last Ride," Broadway at Mills Street, July 1, 1950, public domain archival image

Following the end of streetcar service, the entire 175-car fleet was sent to a scrapyard and burned in a massive bonfire. In the years that followed, and especially after the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1959, Buffalo's upward trajectory began to falter. The city plunged into a sustained era of decline as the city centre hollowed out between the 1960s and 1980s. Furthermore, the lack of adequate public transportation and a proliferation of suburban sprawl caused the old commercial avenues and neighbourhoods along former streetcar routes to vanish, and Buffalo's major arteries deteriorated into rows of empty storefronts and parking lots.

Broadway at Mills as it appears today, image via Google Street View

Broadway at Mills as it appears today, image via Google Street View

However, in 1975, 25 years after the last streetcars rolled through downtown Buffalo, the city made a decision that was virtually unprecedented in North America at the time. They decided to bring back the streetcar with the construction of the 10-kilometre Metro Rail line between 1979 and 1986. Featuring a single route along Main Street, the current streetcar runs primarily below ground outside of the downtown core as a light metro for 8.4 kilometres, and the remaining 1.6 kilometres operate as an above-ground LRT, travelling through the considerably denser, more pedestrian-friendly section of Main Street that runs through downtown.

Buffalo Metro Rail, University Station, image by Flickr user Dottie Mae via Creative Commons

Buffalo Metro Rail, University Station, image by Flickr user Dottie Mae via Creative Commons

From its debut in 1986 until 2008, the downtown portion of Main Street where the Metro Rail line travels above ground was closed to regular vehicle traffic. The downtown commercial strip operated as a pedestrian transit mall for the first 20 years of its existence. After a series of public consultations, the street was reopened to limited car traffic, which owing to the demands of local businesses, once more allowed on-street parking. The result is what urban planners refer to as a "complete street," which has led to a recent boom for local businesses, and for downtown Buffalo in general.

Buffalo Metro Rail, Downtown Main Street, image by David Wilson via Wikimedia Commons

Buffalo Metro Rail, Downtown Main Street, image by David Wilson via Wikimedia Commons

In light of the recent success of the Metro Rail, which ran at subpar ridership numbers for its first two decades, there are now plans in the works to expand the network with future service to the airport, as well as the return of service to a handful of formerly abandoned streetcar routes over the course of the next decade. While the current 10-kilometre light rail network pales in comparison to the original system, the recent uptick in public support and enthusiasm for a return to light rail in the city will more than likely set Buffalo on a path for success. The downtown renaissance now occurring in the city could once again restore the Queen City as the jewel in the crown of Western New York.

SkyriseCities will return soon with a new edition of Once Upon a Tram, which will take an in-depth look at the transit legacy of a city near you. In the meantime, feel free to join the conversation in the comments section below. Got an idea for this series? Let us know!

22K

22K