You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

- Thread starter jahvon09

- Start date

bennessb

editor at large

thanks for the indoor shots, @towerpower123!

towerpower123

Senior Member

Tentative opening date for the interior of the main hall is in March, as in next month. The exact day is unknown, and will likely be known hours before knowing the PA. The entire transit hub, excluding the third platform, will then be opened to the public. The retail will take longer as the tenants still have to fit out their spaces.

bennessb

editor at large

let us know if you hear anything!

towerpower123

Senior Member

The Oculus will officially open the first week of March.

http://ny.curbed.com/archives/2016/..._oculus_will_open_the_first_week_in_march.php

http://ny.curbed.com/archives/2016/..._oculus_will_open_the_first_week_in_march.php

bennessb

editor at large

can't wait to see that, @towerpower123!

Davidackerman

Active Member

Heres a story and interview with Calatrava from WSJ

Trade Center Hub

The architect on the opening of his biggest U.S. project yet: New York’s World Trade Center Transportation Hub, which took more than 10 years and nearly $4 billion to complete

ByALEXANDRA WOLFE

Feb. 26, 2016 9:49 a.m. ET

As architect Santiago Calatrava was designing the World Trade Center Transportation Hub in lower Manhattan, his priority, he says, was to make it the sort of place that his late mother could have navigated. Admittedly, the building’s extravagant design doesn’t immediately prompt such thoughts: Its centerpiece structure, the Oculus, features soaring white wings that rise, birdlike, into the air and a retractable skylight. But Mr. Calatrava says that he always had simplicity in mind.

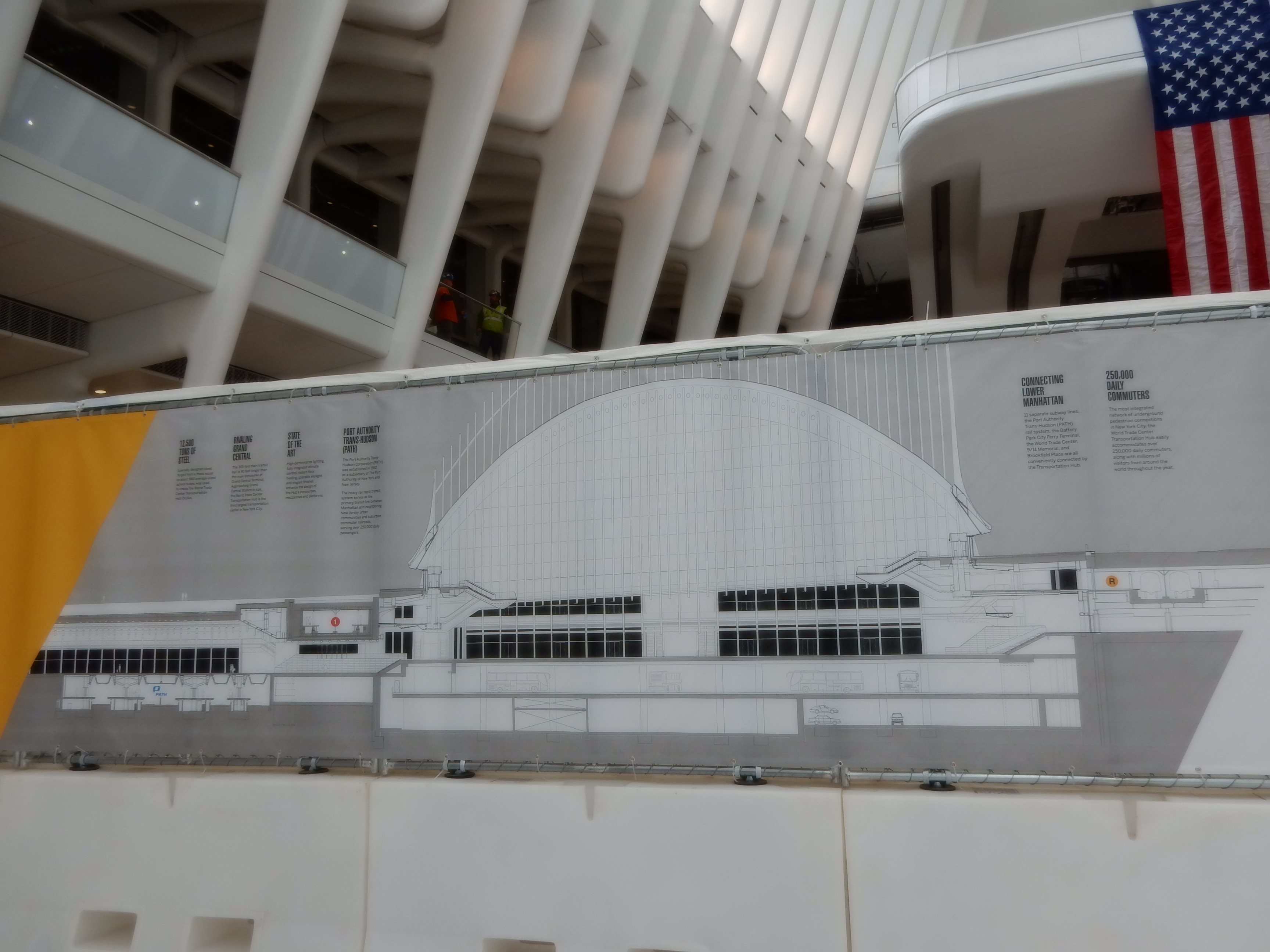

When it opens the first week of March, the 150-foot-tall structure will connect 11 subway lines with a commuter train, several bus routes, ferry service and parking garages, with more than 250,000 commuters expected to come through every day. The complex, Mr. Calatrava says, “has a serious character but is very calm”—even if its construction was anything but that. The new hub has taken more than 10 years and nearly $4 billion to complete, twice the estimated time and cost.

It will be the architect’s highest-profile U.S. work to date. Known for hisdramatic, sculptural structures, Mr. Calatrava, 64, is often inspired by shapes in nature. His previous structures include the Turning Torso in Malmo, Sweden, a building that twists as it rises; the Quadracci Pavilion at the Milwaukee Art Museum; and the harplike Alamillo Bridge in Santiago, Spain. Last fall, he won the European Prize for Architecture.

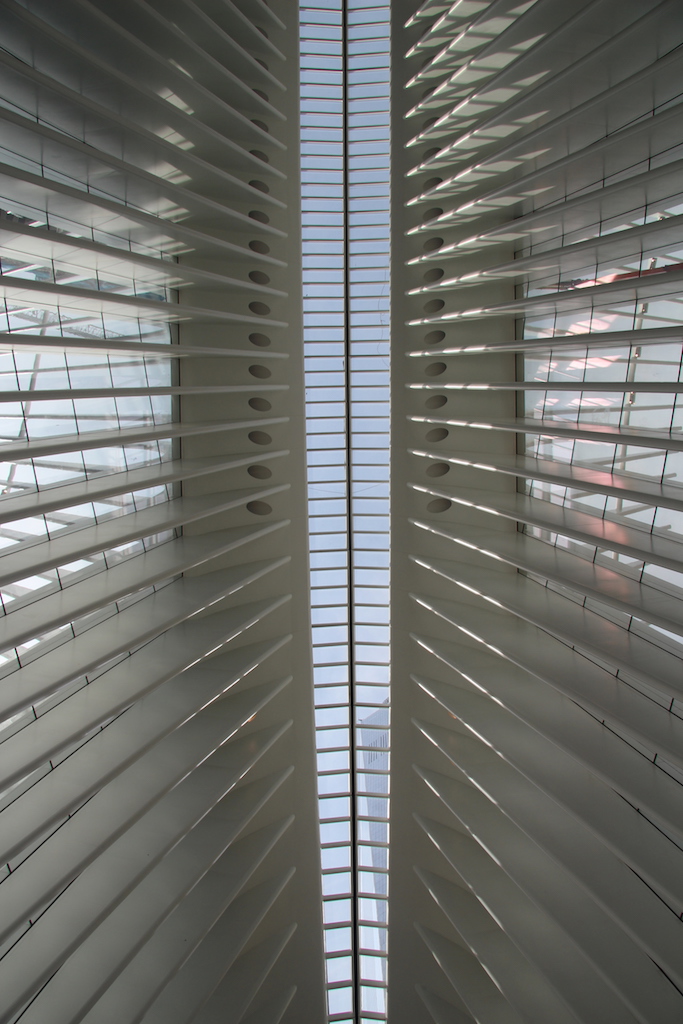

Mr. Calatrava hopes that visitors will feel uplifted by his latest creation. The brilliant white steel arches of the building’s exterior sit atop a light-filled main concourse, clad in white marble and steel. It calls to mind the interior of a massive cathedral, albeit one lined with retail stores. The goal, he says, is for each commuter to feel, “This station is built for me.” Good design inspires people to be respectful, he adds: “If you have a beautiful station, the station remains clean and has better security.”

When Mr. Calatrava was pitching his ideas for the commission to the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, he wanted to think of a way that the site could respond to the attacks of 9/11. He came up with the idea of a child releasing a dove into the air—an image that he thought would offer optimism and hope. “It was a message of faith in the future,” he says.

Yet his reputation suffered during construction, as he came under fire for the cost overruns and delays. Critics said that his design was too complex, his materials too costly: It will be the most expensive train station ever built.

The ‘Oculus’ at the World Trade Center

Commuters looking skyward get grand views at new World Trade Center train station

The main concourse of the World Trade Center Transportation Hub, which will open on a yet-to-be announced date the first week of March.CLAUDIO PAPAPIETRO FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The ‘Oculus’ of arched steel ribs and glass was designed by the Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava to resemble a bird flying out of ...

A worker cleans the windows between the ribs of the Oculus of the World Trade Center Transportation Hub on Friday. CLAUDIO PAPAPIETRO FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The centerpiece of a transit hub linking the PATH and New York City subways is set to open early next month. CLAUDIO PAPAPIETRO FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The windows and ribs of the ceiling of the Oculus. CLAUDIO PAPAPIETRO FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The project is long delayed and about $2 billion over budget. CLAUDIO PAPAPIETRO FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Stores and restaurants are expected to open in the new transportation hub. CLAUDIO PAPAPIETRO FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

‘We tried to do something that inspires optimism,’ says architect Santiago Calatrava. CLAUDIO PAPAPIETRO FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

An exterior view of the Oculus. CLAUDIO PAPAPIETRO FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The main concourse of the World Trade Center Transportation Hub, which will open on a yet-to-be announced date the first week of March.CLAUDIO PAPAPIETRO FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The ‘Oculus’ of arched steel ribs and glass was designed by the Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava to resemble a bird flying out of child’s hand, a symbol of hope for a scarred city. CLAUDIO PAPAPIETRO FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Mr. Calatrava thinks that the criticism has been unfair. “The beautiful is difficult,” he says, adding that it’s particularly hard to control budgets with railway projects because of their complexity. Part of the problem with the World Trade Center hub was that multiple rival agencies were involved; local officials also decided to keep a subway line underneath the construction operational rather than close it down temporarily, adding to the costs and logistical issues.

The hub will be the eighth railway station that Mr. Calatrava has built. The others, including the Oriente metro station in Lisbon, Portugal, and the Liège-Guillemins station in Belgium, are in Europe. Train stations there, he says, used to be lofty, airy places so that the train’s steam had ample room to be released. Although steam is no longer an issue, he still likes to celebrate that open feel.

Mr. Calatrava was born in Valencia, Spain, to a family that worked in agricultural exports. In college, he studied both architecture and engineering. Today, he and his wife, Robertina, who runs the business side of his practice, live mainly between New York and Zurich. He also has an office in Doha, Qatar, that his son Micael opened. Of his three other children, another son, Gabriel, has his own architectural practice. His son has found success on his own, he says, but “sometimes it is difficult when your father is in front of you and occupying so much space.”

The advice he gives to all of his children is to persevere. He thinks that the people he admires most in his profession—I.M. Pei, Le Corbusier, Eero Saarinen—produced their best work later in life. “You need to know a lot to become master of your profession,” he says.

These days, Mr. Calatrava has settled into a routine. He usually wakes up at 6 a.m. and exercises for an hour, then walks his dog. By 7:45 he’s ready to go to his studio. He is an artist as well as an architect, and he likes to spend his mornings drawing. After lunch at noon he heads to his office, where he works until 7 or 8.

Lately, he’s spent most of his time in New York as he gears up for the opening of the downtown hub. New York, he thinks, is the most exciting city right now in both architecture and art. “Often I compare New York to Paris at the turn of the [20th] century,” he says. “You can meet a lot of artists here.”

Completing the hub is bittersweet. “The architect works for so many years building it, and the moment you deliver it to the people is the moment when you are unnecessary,” he says with a smile.

Just as Grand Central Terminal has endured for over a century, he hopes the hub will be around for a long time. There’s only one problem. “This station is a milestone” in his career, he says. “What can I do now?”

Trade Center Hub

The architect on the opening of his biggest U.S. project yet: New York’s World Trade Center Transportation Hub, which took more than 10 years and nearly $4 billion to complete

ByALEXANDRA WOLFE

Feb. 26, 2016 9:49 a.m. ET

As architect Santiago Calatrava was designing the World Trade Center Transportation Hub in lower Manhattan, his priority, he says, was to make it the sort of place that his late mother could have navigated. Admittedly, the building’s extravagant design doesn’t immediately prompt such thoughts: Its centerpiece structure, the Oculus, features soaring white wings that rise, birdlike, into the air and a retractable skylight. But Mr. Calatrava says that he always had simplicity in mind.

When it opens the first week of March, the 150-foot-tall structure will connect 11 subway lines with a commuter train, several bus routes, ferry service and parking garages, with more than 250,000 commuters expected to come through every day. The complex, Mr. Calatrava says, “has a serious character but is very calm”—even if its construction was anything but that. The new hub has taken more than 10 years and nearly $4 billion to complete, twice the estimated time and cost.

It will be the architect’s highest-profile U.S. work to date. Known for hisdramatic, sculptural structures, Mr. Calatrava, 64, is often inspired by shapes in nature. His previous structures include the Turning Torso in Malmo, Sweden, a building that twists as it rises; the Quadracci Pavilion at the Milwaukee Art Museum; and the harplike Alamillo Bridge in Santiago, Spain. Last fall, he won the European Prize for Architecture.

Mr. Calatrava hopes that visitors will feel uplifted by his latest creation. The brilliant white steel arches of the building’s exterior sit atop a light-filled main concourse, clad in white marble and steel. It calls to mind the interior of a massive cathedral, albeit one lined with retail stores. The goal, he says, is for each commuter to feel, “This station is built for me.” Good design inspires people to be respectful, he adds: “If you have a beautiful station, the station remains clean and has better security.”

When Mr. Calatrava was pitching his ideas for the commission to the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, he wanted to think of a way that the site could respond to the attacks of 9/11. He came up with the idea of a child releasing a dove into the air—an image that he thought would offer optimism and hope. “It was a message of faith in the future,” he says.

Yet his reputation suffered during construction, as he came under fire for the cost overruns and delays. Critics said that his design was too complex, his materials too costly: It will be the most expensive train station ever built.

The ‘Oculus’ at the World Trade Center

Commuters looking skyward get grand views at new World Trade Center train station

The main concourse of the World Trade Center Transportation Hub, which will open on a yet-to-be announced date the first week of March.CLAUDIO PAPAPIETRO FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The ‘Oculus’ of arched steel ribs and glass was designed by the Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava to resemble a bird flying out of ...

A worker cleans the windows between the ribs of the Oculus of the World Trade Center Transportation Hub on Friday. CLAUDIO PAPAPIETRO FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The centerpiece of a transit hub linking the PATH and New York City subways is set to open early next month. CLAUDIO PAPAPIETRO FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The windows and ribs of the ceiling of the Oculus. CLAUDIO PAPAPIETRO FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The project is long delayed and about $2 billion over budget. CLAUDIO PAPAPIETRO FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Stores and restaurants are expected to open in the new transportation hub. CLAUDIO PAPAPIETRO FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

‘We tried to do something that inspires optimism,’ says architect Santiago Calatrava. CLAUDIO PAPAPIETRO FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

An exterior view of the Oculus. CLAUDIO PAPAPIETRO FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The main concourse of the World Trade Center Transportation Hub, which will open on a yet-to-be announced date the first week of March.CLAUDIO PAPAPIETRO FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The ‘Oculus’ of arched steel ribs and glass was designed by the Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava to resemble a bird flying out of child’s hand, a symbol of hope for a scarred city. CLAUDIO PAPAPIETRO FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Mr. Calatrava thinks that the criticism has been unfair. “The beautiful is difficult,” he says, adding that it’s particularly hard to control budgets with railway projects because of their complexity. Part of the problem with the World Trade Center hub was that multiple rival agencies were involved; local officials also decided to keep a subway line underneath the construction operational rather than close it down temporarily, adding to the costs and logistical issues.

The hub will be the eighth railway station that Mr. Calatrava has built. The others, including the Oriente metro station in Lisbon, Portugal, and the Liège-Guillemins station in Belgium, are in Europe. Train stations there, he says, used to be lofty, airy places so that the train’s steam had ample room to be released. Although steam is no longer an issue, he still likes to celebrate that open feel.

Mr. Calatrava was born in Valencia, Spain, to a family that worked in agricultural exports. In college, he studied both architecture and engineering. Today, he and his wife, Robertina, who runs the business side of his practice, live mainly between New York and Zurich. He also has an office in Doha, Qatar, that his son Micael opened. Of his three other children, another son, Gabriel, has his own architectural practice. His son has found success on his own, he says, but “sometimes it is difficult when your father is in front of you and occupying so much space.”

The advice he gives to all of his children is to persevere. He thinks that the people he admires most in his profession—I.M. Pei, Le Corbusier, Eero Saarinen—produced their best work later in life. “You need to know a lot to become master of your profession,” he says.

These days, Mr. Calatrava has settled into a routine. He usually wakes up at 6 a.m. and exercises for an hour, then walks his dog. By 7:45 he’s ready to go to his studio. He is an artist as well as an architect, and he likes to spend his mornings drawing. After lunch at noon he heads to his office, where he works until 7 or 8.

Lately, he’s spent most of his time in New York as he gears up for the opening of the downtown hub. New York, he thinks, is the most exciting city right now in both architecture and art. “Often I compare New York to Paris at the turn of the [20th] century,” he says. “You can meet a lot of artists here.”

Completing the hub is bittersweet. “The architect works for so many years building it, and the moment you deliver it to the people is the moment when you are unnecessary,” he says with a smile.

Just as Grand Central Terminal has endured for over a century, he hopes the hub will be around for a long time. There’s only one problem. “This station is a milestone” in his career, he says. “What can I do now?”

gabe

Senior Member

Can't wait to see this in person. Thanks for the indoor pics.

Some video and pics here http://www.aol.com/article/2016/03/...b-to-open-a-new-york-phoenix-rising/21320815/

Some video and pics here http://www.aol.com/article/2016/03/...b-to-open-a-new-york-phoenix-rising/21320815/

towerpower123

Senior Member

Official Opening Date is March 4th, this Friday, barring any unforeseen problems. There will not be an opening ceremony due to costs...

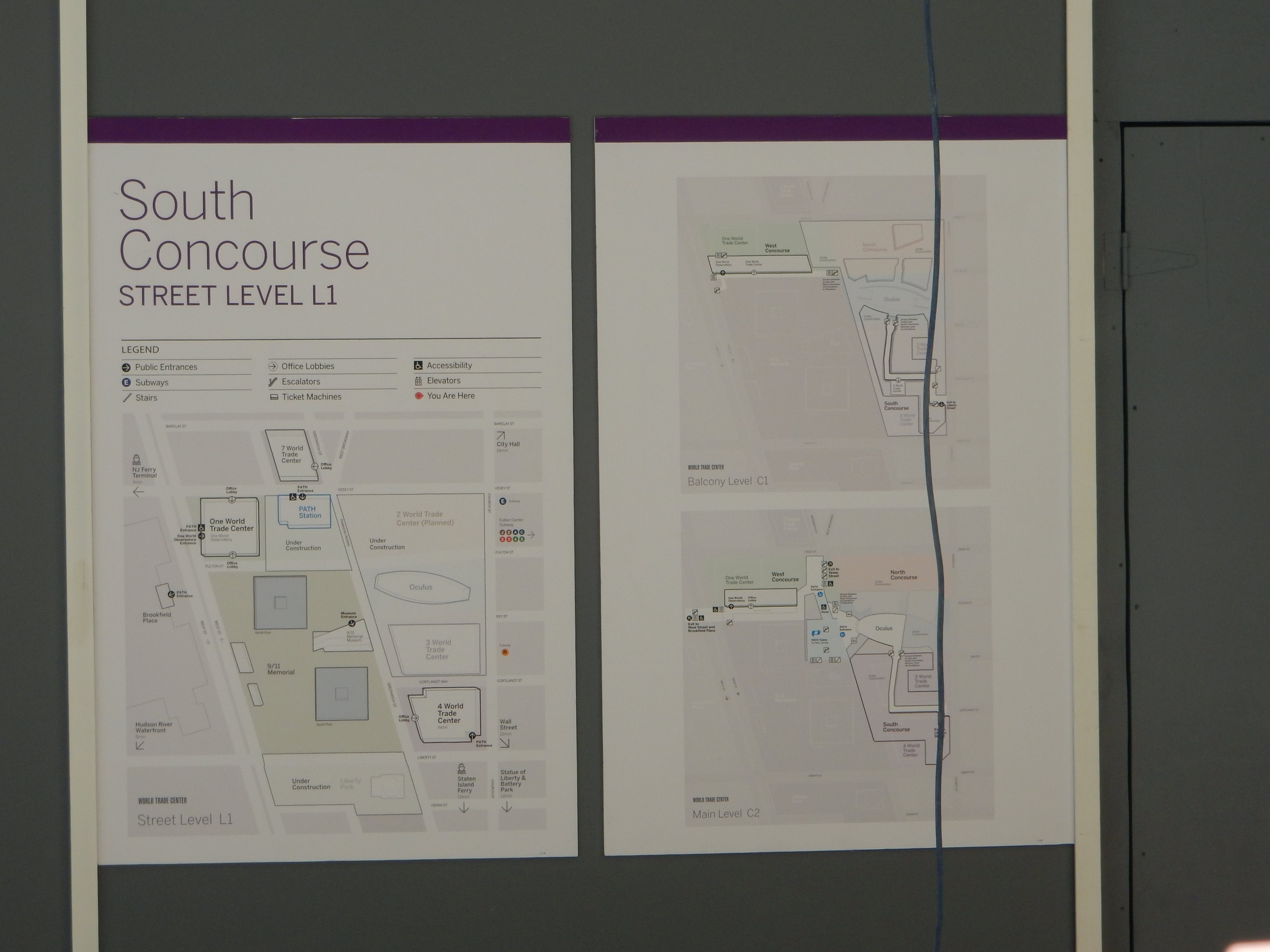

A map installed in the Four World Trade Center Entrance shows the new fence layout and what will be accessible when it opens Friday. The intended entrance directly into the ends of the Oculus will apparantly NOT be opened as they will still be fenced off. The only new entrance is through 4 WTC, which will access half of the Oculus and one of the balconies. Currently only the portion to the left of, and not including the Oculus is accessible.

A map installed in the Four World Trade Center Entrance shows the new fence layout and what will be accessible when it opens Friday. The intended entrance directly into the ends of the Oculus will apparantly NOT be opened as they will still be fenced off. The only new entrance is through 4 WTC, which will access half of the Oculus and one of the balconies. Currently only the portion to the left of, and not including the Oculus is accessible.

Attachments

Last edited:

bennessb

editor at large

Lot of news stories & commentary this week!

Santiago Calatrava’s Transit Hub Is a Soaring Symbol of a Boondoggle (New York Times)

With the Opening of the WTC Transportation Hub, Has Santiago Calatrava Been Vindicated? (ArchDaily)

A Long Chat With Santiago Calatrava on What Train Stations Mean to Cities (CityLab)

Santiago Calatrava’s Transit Hub Is a Soaring Symbol of a Boondoggle (New York Times)

With the Opening of the WTC Transportation Hub, Has Santiago Calatrava Been Vindicated? (ArchDaily)

A Long Chat With Santiago Calatrava on What Train Stations Mean to Cities (CityLab)

towerpower123

Senior Member

The Oculus is half open and the double level corridor to Four World Trade Center. It will eventually be retail behind all of the gray walls. The second level and the connection to the subways (through the other side of the Oculus), the entrances to the Oculus, and the third patform are not yet open. They will open in stages in the future, with the entire thing complete by December 2016 or January 2017.

Attachments

-

DSCN5246.JPG597.7 KB · Views: 252

DSCN5246.JPG597.7 KB · Views: 252 -

DSCN5248.JPG577.2 KB · Views: 231

DSCN5248.JPG577.2 KB · Views: 231 -

DSCN5253.JPG578.7 KB · Views: 226

DSCN5253.JPG578.7 KB · Views: 226 -

DSCN5255.JPG537.2 KB · Views: 232

DSCN5255.JPG537.2 KB · Views: 232 -

DSCN5257.JPG554 KB · Views: 267

DSCN5257.JPG554 KB · Views: 267 -

DSCN5258.JPG616.6 KB · Views: 213

DSCN5258.JPG616.6 KB · Views: 213 -

DSCN5260.JPG634.1 KB · Views: 225

DSCN5260.JPG634.1 KB · Views: 225 -

DSCN5261.JPG642.8 KB · Views: 224

DSCN5261.JPG642.8 KB · Views: 224 -

DSCN5263.JPG616.4 KB · Views: 222

DSCN5263.JPG616.4 KB · Views: 222 -

DSCN5264.JPG723.7 KB · Views: 243

DSCN5264.JPG723.7 KB · Views: 243 -

DSCN5267.JPG661.9 KB · Views: 228

DSCN5267.JPG661.9 KB · Views: 228 -

DSCN5271.JPG567.6 KB · Views: 313

DSCN5271.JPG567.6 KB · Views: 313

towerpower123

Senior Member

Transit Hub opening part 2

Attachments

-

DSCN5272.JPG543.8 KB · Views: 254

DSCN5272.JPG543.8 KB · Views: 254 -

DSCN5274.JPG473.3 KB · Views: 219

DSCN5274.JPG473.3 KB · Views: 219 -

DSCN5276.JPG565.9 KB · Views: 237

DSCN5276.JPG565.9 KB · Views: 237 -

DSCN5279.JPG592.9 KB · Views: 220

DSCN5279.JPG592.9 KB · Views: 220 -

DSCN5280.JPG603.2 KB · Views: 222

DSCN5280.JPG603.2 KB · Views: 222 -

DSCN5281.JPG647.5 KB · Views: 225

DSCN5281.JPG647.5 KB · Views: 225 -

DSCN5285.JPG540.3 KB · Views: 229

DSCN5285.JPG540.3 KB · Views: 229 -

DSCN5286.JPG568.6 KB · Views: 218

DSCN5286.JPG568.6 KB · Views: 218 -

DSCN5288.JPG556.9 KB · Views: 249

DSCN5288.JPG556.9 KB · Views: 249 -

DSCN5290.JPG548.4 KB · Views: 267

DSCN5290.JPG548.4 KB · Views: 267 -

DSCN5292.JPG530.5 KB · Views: 227

DSCN5292.JPG530.5 KB · Views: 227 -

DSCN5293.JPG546.5 KB · Views: 210

DSCN5293.JPG546.5 KB · Views: 210 -

DSCN5294.JPG595.7 KB · Views: 214

DSCN5294.JPG595.7 KB · Views: 214 -

DSCN5301.JPG413.5 KB · Views: 208

DSCN5301.JPG413.5 KB · Views: 208 -

DSCN5303.JPG797.7 KB · Views: 217

DSCN5303.JPG797.7 KB · Views: 217

salsa

Senior Member

towerpower123

Senior Member

Attachments

-

DSCN6533.JPG916.6 KB · Views: 196

DSCN6533.JPG916.6 KB · Views: 196 -

DSCN6539.JPG924 KB · Views: 211

DSCN6539.JPG924 KB · Views: 211 -

DSCN6564.JPG944.9 KB · Views: 207

DSCN6564.JPG944.9 KB · Views: 207 -

DSCN6567.JPG873.8 KB · Views: 210

DSCN6567.JPG873.8 KB · Views: 210 -

DSCN6568.JPG774.3 KB · Views: 237

DSCN6568.JPG774.3 KB · Views: 237 -

DSCN6570.JPG816.5 KB · Views: 215

DSCN6570.JPG816.5 KB · Views: 215 -

DSCN6571.JPG737.2 KB · Views: 193

DSCN6571.JPG737.2 KB · Views: 193 -

DSCN6572.JPG859.8 KB · Views: 200

DSCN6572.JPG859.8 KB · Views: 200 -

DSCN6573.JPG874.7 KB · Views: 201

DSCN6573.JPG874.7 KB · Views: 201 -

DSCN6576.JPG876.6 KB · Views: 193

DSCN6576.JPG876.6 KB · Views: 193 -

DSCN6577.JPG826.5 KB · Views: 191

DSCN6577.JPG826.5 KB · Views: 191 -

DSCN6578.JPG974.5 KB · Views: 219

DSCN6578.JPG974.5 KB · Views: 219 -

DSCN6580.JPG763 KB · Views: 193

DSCN6580.JPG763 KB · Views: 193 -

DSCN6583.JPG688.2 KB · Views: 180

DSCN6583.JPG688.2 KB · Views: 180 -

DSCN6585.JPG797.8 KB · Views: 168

DSCN6585.JPG797.8 KB · Views: 168

Fabulous looking. Going to be great when fully open and fully in use.

Attachments

-

IMG_8198 copy.JPG376.3 KB · Views: 158

IMG_8198 copy.JPG376.3 KB · Views: 158 -

IMG_8199 copy.JPG260.8 KB · Views: 179

IMG_8199 copy.JPG260.8 KB · Views: 179 -

IMG_8206 copy.JPG318.1 KB · Views: 185

IMG_8206 copy.JPG318.1 KB · Views: 185 -

IMG_8208 copy.JPG251.7 KB · Views: 189

IMG_8208 copy.JPG251.7 KB · Views: 189 -

IMG_8212 copy.JPG442.5 KB · Views: 179

IMG_8212 copy.JPG442.5 KB · Views: 179 -

IMG_8220 copy.JPG340.9 KB · Views: 158

IMG_8220 copy.JPG340.9 KB · Views: 158 -

IMG_8221 copy.JPG416.9 KB · Views: 171

IMG_8221 copy.JPG416.9 KB · Views: 171 -

IMG_8224 copy.JPG411.4 KB · Views: 173

IMG_8224 copy.JPG411.4 KB · Views: 173 -

IMG_8230 copy.JPG329.3 KB · Views: 176

IMG_8230 copy.JPG329.3 KB · Views: 176 -

IMG_8231 copy.JPG417.3 KB · Views: 157

IMG_8231 copy.JPG417.3 KB · Views: 157 -

IMG_8234 copy.JPG260.9 KB · Views: 151

IMG_8234 copy.JPG260.9 KB · Views: 151 -

IMG_8236 copy.JPG314 KB · Views: 166

IMG_8236 copy.JPG314 KB · Views: 166 -

IMG_8238 copy.JPG287.5 KB · Views: 162

IMG_8238 copy.JPG287.5 KB · Views: 162 -

IMG_8241 copy.JPG384.9 KB · Views: 157

IMG_8241 copy.JPG384.9 KB · Views: 157 -

IMG_8243 copy.JPG286.7 KB · Views: 156

IMG_8243 copy.JPG286.7 KB · Views: 156