|

|

|

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

- Thread starter hoggytime

- Start date

From the Ottawa Citizen:

Author of the article:

Brigitte Pellerin

Published Feb 23, 2024 • Last updated 8 hours ago • 3 minute read

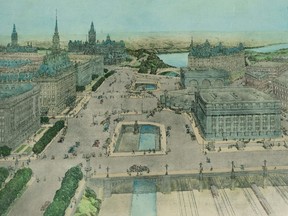

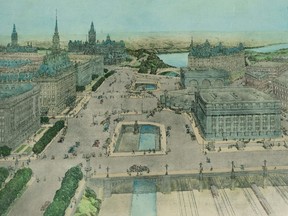

The image the NCC used on X (formerly twitter) shows an open pedestrian plaza down the street from Parliament Hill. Photo by National Capital Commission

The image the NCC used on X (formerly twitter) shows an open pedestrian plaza down the street from Parliament Hill. Photo by National Capital Commission

OK, so the post was trying to generate some interest for a public talk held Feb. 22 on the Beautiful Capital, featuring my old friend who also happens to be NCC vice-president and chief planner, Alain Miguelez. Still, I asked myself. What if … yeah, what if we’d adopted the Holt-Bennett Plan of 1915?

The very first step, of course, was to confess to not having the faintest clue what the Holt-Bennett Plan of 1915 was. And no wonder; it was shelved shortly after it was tabled (so many furniture-related metaphors) and has been collecting dust for more than a century. If you google even just a little, you will find that some people in Ottawa are far more knowledgeable about this than yours truly, and have written very interesting things about it.

The man behind the plan, which was for both Ottawa and what was then Hull, was Edward Bennett, described as a leading “City Beautiful architect.” That led straight to my second confession: I’d never heard the term “City Beautiful architect” before.

I learned that City Beautiful was a movement invented in the United States to beautify cities, which, at the time, were overcrowded with factory workers and not always very clean or pleasant. Originally associated with Chicago (Bennett, it is worth noting, co-wrote the 1909 Plan of Chicago), the movement flourished in the 1890s and 1900s and was based on the belief that beautification would lead to harmonious societies and better quality of life. Critics such as Jane Jacobs, who reportedly called it a “cult,” thought it favoured esthetics over social reform.

What I want to know is why we should have to choose between the two?

The attention-grabbing image in the plan, known as Illustration #5, is the one that shows a view of the proposed space between and around Parliament and the old rail station that is open to people and is vaguely reminiscent of the Mall in Washington, D.C., with lovely public places and basic amenities such as public toilets. Every time I visit the American capital, I ask why we can’t have that here.

Apparently it’s too hard. We threw away the one opportunity we had to make something other than a car tunnel out of Wellington Street by doing nothing whatsoever with the space after we closed it to motor vehicles following the convoy protest. Just last week, the city released statistics showing vehicular traffic was almost back to pre-pandemic levels. This left Coun. Tim Tierney, chair of the transportation committee, feeling awesome. “People are very happy,” he said. “They don’t have to take that extra commute through Gatineau to be able to get to the other side of Ottawa.” Someone please send the councillor a map of downtown Ottawa that shows all the east-west streets that aren’t Wellington.

The most beautiful thing about the Holt-Bennett Plan is that it was comprehensive and looked at the growth of the area in a holistic manner. It connected things — places to be with places to live and places to work, and it put humans first. Edward Bennett understood that sustainable growth could not happen without robust public transit. But he was not against other forms of transportation, not even private motor vehicles. It was a balanced approach.

We never implemented his plan. Instead, we eventually went with the 1950 Gréber Plan that replaced rail with parkways, led to the horrendous Queensway and distributed federal departments all over everywhere, encouraging sprawl.

Maybe it’s time to dust off Edward Bennett’s old document and dare to let it inspire us.

Brigitte Pellerin (they/them) is an Ottawa writer.

Pellerin: 1915 — when a better plan for Ottawa existed

You've never heard of the Holt-Bennett Plan either? It just might have given us a beautiful — and functional — urban landscape.Author of the article:

Brigitte Pellerin

Published Feb 23, 2024 • Last updated 8 hours ago • 3 minute read

Last weekend, the National Capital Commission got my attention on social networks. “Have you heard of the Holt-Bennett Plan of 1915? Had it been carried out, Ottawa would have looked like a European capital, had its first subway line, and mapped its growth differently,” the X-tweet said, alongside a wonderful image of a pedestrian plaza near Parliament Hill.OK, so the post was trying to generate some interest for a public talk held Feb. 22 on the Beautiful Capital, featuring my old friend who also happens to be NCC vice-president and chief planner, Alain Miguelez. Still, I asked myself. What if … yeah, what if we’d adopted the Holt-Bennett Plan of 1915?

The very first step, of course, was to confess to not having the faintest clue what the Holt-Bennett Plan of 1915 was. And no wonder; it was shelved shortly after it was tabled (so many furniture-related metaphors) and has been collecting dust for more than a century. If you google even just a little, you will find that some people in Ottawa are far more knowledgeable about this than yours truly, and have written very interesting things about it.

The man behind the plan, which was for both Ottawa and what was then Hull, was Edward Bennett, described as a leading “City Beautiful architect.” That led straight to my second confession: I’d never heard the term “City Beautiful architect” before.

I learned that City Beautiful was a movement invented in the United States to beautify cities, which, at the time, were overcrowded with factory workers and not always very clean or pleasant. Originally associated with Chicago (Bennett, it is worth noting, co-wrote the 1909 Plan of Chicago), the movement flourished in the 1890s and 1900s and was based on the belief that beautification would lead to harmonious societies and better quality of life. Critics such as Jane Jacobs, who reportedly called it a “cult,” thought it favoured esthetics over social reform.

What I want to know is why we should have to choose between the two?

The attention-grabbing image in the plan, known as Illustration #5, is the one that shows a view of the proposed space between and around Parliament and the old rail station that is open to people and is vaguely reminiscent of the Mall in Washington, D.C., with lovely public places and basic amenities such as public toilets. Every time I visit the American capital, I ask why we can’t have that here.

Apparently it’s too hard. We threw away the one opportunity we had to make something other than a car tunnel out of Wellington Street by doing nothing whatsoever with the space after we closed it to motor vehicles following the convoy protest. Just last week, the city released statistics showing vehicular traffic was almost back to pre-pandemic levels. This left Coun. Tim Tierney, chair of the transportation committee, feeling awesome. “People are very happy,” he said. “They don’t have to take that extra commute through Gatineau to be able to get to the other side of Ottawa.” Someone please send the councillor a map of downtown Ottawa that shows all the east-west streets that aren’t Wellington.

The most beautiful thing about the Holt-Bennett Plan is that it was comprehensive and looked at the growth of the area in a holistic manner. It connected things — places to be with places to live and places to work, and it put humans first. Edward Bennett understood that sustainable growth could not happen without robust public transit. But he was not against other forms of transportation, not even private motor vehicles. It was a balanced approach.

We never implemented his plan. Instead, we eventually went with the 1950 Gréber Plan that replaced rail with parkways, led to the horrendous Queensway and distributed federal departments all over everywhere, encouraging sprawl.

Maybe it’s time to dust off Edward Bennett’s old document and dare to let it inspire us.

Brigitte Pellerin (they/them) is an Ottawa writer.

Ottawater

New Member

I always wonder if big plazas as centre pieces are suited to our wind swept winters…

I've walked around Parc Jean-Drapeau in the winter once.... 0/10, don't recommendI always wonder if big plazas as centre pieces are suited to our wind swept winters…