lansd

New Member

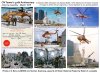

Building the CN Tower’s Antenna Components – 1971 through 1975

In 1971 CANRON Inc. (Etobicoke, ON) received multiple contracts from the Foundation Co. of Canada to fabricate and install the CN Tower’s antenna as well as the steel work for the restaurant pod and upper, interior stair cases. The construction and installation of the antenna was an engineering feat never attempted before. It would require a 335ft steel-plate bolted antenna of 300 tons to be erected at the 1500ft level. The CN Tower faced many engineering roadblocks but one of the most difficult to solve was “How are we going to get a 300 ton, 335 foot steel antenna to the top of small concrete mound at the 1500ft level?”.

An excellent historical record of this work was documented in a 16mm film made by Chris Slagter (CSC), commissioned entirely by CANRON and without any financial support from the Foundation Co. (now AECON). Chris died on May 13th 2003 at age 80 (it had been said he became a church minister in his latter years). A somewhat poor copy of the film can be seen online at the YouTube link:

Ultimately, as the story unfolds, a Sikorsky S-64E helicopter was leased to haul up the antenna in 39 sections, each weighing no more than 8 tons each. They varied in diameter from 12 feet at the base of the antenna to a slim 2 feet at the top, with the metal’s thickness varying from 1.5” to 0.5”. “Spiders” were placed inside the can segments to keep the antenna taut and from twisting. The antenna was fabricated at CANRON’s facility on Disco Rd. in Etobicoke, as shown in the lower left image where the can segments were being pre-assembled. The segments were pre-painted white (except at the junctions, which as their unpainted zinc coating until painter Tony Tracey came back later to paint those sections white, up on the tower). The antenna segments were made from “Stelcoly 50”, a high strength, low alloy, fine grained steel manufactured by Stelco in Canada.

CANRON’s Jerry Morrow designed the “working platform”, as shown in the lower middle image, which was placed around the antenna to act as protection and a staging area for CANRON’s iron worker bolting gangs. It would be ratcheted up the antenna, by hand cranks, as the bolting gang completed their bolting & torquing work on each can segment.

As a gesture of goodwill and a small marketing stunt, CANRON trucked the topmost 32 foot segment of the antenna down to the (new) Harbourfront area on March 20th 1975 (on display until March 27th) where Torontonians were allowed to sign their name on the segment. It was estimated that 7000 people, including bus loads of school children, got the honour of putting their name on one of the highest human-made objects on this planet. These names can be partially seen in the right-most two images of this collage.

-------------------

One of the most fundamentally important yet unknown stories related to the CN Tower’s construction was that of a young 23 year old University of Wateloo Co-Op student (Jerry Morrow) who solved one of the greatest engineering debacles of the tower’s antenna installation….

During 17 hours of initial interviews, CANRON came to recount the evolution of the CN Tower's antenna design and erection. When CANRON was given the contract to raise the steel in 1971, its engineers planned to build the antenna right inside the tower and jack it up through the top at the tower's concrete shaft at the 1500ft level. Three antenna designs were made and each rejected. In October 1973 (although stated as June 1973 by account of a March 22nd 1975 Toronto Star article), Wayne Baigent (CANRON’s engineering manager) chose to construct and hoist up a lattice (tubular design) antenna frame via a jib crane, piece by piece. While this was deemed a good and acceptable design, it would have resulted in an antenna core which could twist and bend more easily than a rigid steel structure. As fate would have it, the appropriate quantities of metal were not available to fabricate the tubular antenna design.

A young and new recruit, Jerry Morrow, who had been a University of Waterloo CoOp student with CANRON, and now recent full time hire (at age 23, 1974), came up with the alternative design of a rigid low-alloy steel core antenna for the CN Tower, fabricated as 39 metal "can" segments that would be hoisted up and stacked one upon each other. The question remaining was "How were the multi-ton 'can' segments to be hoisted up to the top of the tower, where winds can be quite blustery?". The Foundation Co. had suggested using large weather balloon (as used in logging), tethered to long guide lines to the ground - however, that idea was quickly rejected due to the length of such tethering cables, and the in-ability to attain sufficient precision for placing each segment.

At this time, as an avid reader of the Popular Mechanics magazine, Jerry Morrow had become aware of Erickson Air-Crane Inc. and their primary work of using Sikorsky S-64E helicopters to do logging in Oregon and Washington state. CANRON’s Stu Eccles approached Sikorsky and then the two civilian operators of S-64E's, Everygreen Helicopter of Oregon and Erickson Air-Crane of Marysville, Calfornia. CANRON asked both companies if they would consider taking on the job to remove the CN Tower's crane and make dozens of helicopter lifts to erect the tower's metal-core antenna. It was stated by CANRON that Erickson was reluctant to take on the job, as their main focus was logging and not construction related work. CANRON then approached Sikorsky themselves and sold them about the marketing potential that the CN Tower job would offer to their company and that of Erickson Air-Crane Inc. Tenders were put out to both companies and Erickson came in lower at a flat fee of US$230,000 (1975 dollars) for 36 working days, being used for a period of 22 days. Sikorsky then persuaded Erickson to take on the job, which they did, and to great success to their company and future reputation + marketing. At the time, in 1975, Erickson owned three S-64E helicopters, valued at US$4 million each (1975 dollars).

During the fabrication stages of the antenna cans at CANRON’s Disco Rd facility in Etobicoke, Ontario, it was unclear as to whether a helicopter would actually be used, as that was still not a guarantee during 1972 and 1973. Hence, the antenna mast was designed to be broken down into very basic pieces and re-assembled, piecemeal, by a jib boom crane through human manpower, which may have taken an estimated 6 months to complete vs. the 3-1/2 weeks by helicopter. This answers the basic question of “Why are the can segments bolted together rather than being fully welded?”. The round holes in each can were provided so that EMI of England could install the electronic components of the antenna later on in the year.

CANRON was awarded the Montgomery Memorial Medal for innovation in construction in Canada by the Canadian Construction Assoc. for their work in engineering and erecting the CN Tower’s metal core antenna.

-------------------

The antenna used two static “tuned dampers” to help reduce the sway and natural vibrations of the antenna mast. They were designed by several young Canadian engineers under the guidance of D.L. Allen, a University of Toronto professor, who headed up Vibron Ltd. It is based on the "hula hoop" principle for which the heavily lead-ladden 10 ton "hoops" hang free of the antenna and help to stabilize it. As the antenna hits the hoops, their dead weight helps to "nudge" the antenna back into position – they are allowed to move horizontally to a maximum of 2 feet. The lower damper acts as a pendulum while the upper damper as an inverted pendulum. The first damper was placed 135ft from the base of the antenna mast and the second 50ft higher. CANRON fabricated the 14ft diameter ring for the bottom unit and the 10ft diameter ring for the top unit.

In 1971 CANRON Inc. (Etobicoke, ON) received multiple contracts from the Foundation Co. of Canada to fabricate and install the CN Tower’s antenna as well as the steel work for the restaurant pod and upper, interior stair cases. The construction and installation of the antenna was an engineering feat never attempted before. It would require a 335ft steel-plate bolted antenna of 300 tons to be erected at the 1500ft level. The CN Tower faced many engineering roadblocks but one of the most difficult to solve was “How are we going to get a 300 ton, 335 foot steel antenna to the top of small concrete mound at the 1500ft level?”.

An excellent historical record of this work was documented in a 16mm film made by Chris Slagter (CSC), commissioned entirely by CANRON and without any financial support from the Foundation Co. (now AECON). Chris died on May 13th 2003 at age 80 (it had been said he became a church minister in his latter years). A somewhat poor copy of the film can be seen online at the YouTube link:

Ultimately, as the story unfolds, a Sikorsky S-64E helicopter was leased to haul up the antenna in 39 sections, each weighing no more than 8 tons each. They varied in diameter from 12 feet at the base of the antenna to a slim 2 feet at the top, with the metal’s thickness varying from 1.5” to 0.5”. “Spiders” were placed inside the can segments to keep the antenna taut and from twisting. The antenna was fabricated at CANRON’s facility on Disco Rd. in Etobicoke, as shown in the lower left image where the can segments were being pre-assembled. The segments were pre-painted white (except at the junctions, which as their unpainted zinc coating until painter Tony Tracey came back later to paint those sections white, up on the tower). The antenna segments were made from “Stelcoly 50”, a high strength, low alloy, fine grained steel manufactured by Stelco in Canada.

CANRON’s Jerry Morrow designed the “working platform”, as shown in the lower middle image, which was placed around the antenna to act as protection and a staging area for CANRON’s iron worker bolting gangs. It would be ratcheted up the antenna, by hand cranks, as the bolting gang completed their bolting & torquing work on each can segment.

As a gesture of goodwill and a small marketing stunt, CANRON trucked the topmost 32 foot segment of the antenna down to the (new) Harbourfront area on March 20th 1975 (on display until March 27th) where Torontonians were allowed to sign their name on the segment. It was estimated that 7000 people, including bus loads of school children, got the honour of putting their name on one of the highest human-made objects on this planet. These names can be partially seen in the right-most two images of this collage.

-------------------

One of the most fundamentally important yet unknown stories related to the CN Tower’s construction was that of a young 23 year old University of Wateloo Co-Op student (Jerry Morrow) who solved one of the greatest engineering debacles of the tower’s antenna installation….

During 17 hours of initial interviews, CANRON came to recount the evolution of the CN Tower's antenna design and erection. When CANRON was given the contract to raise the steel in 1971, its engineers planned to build the antenna right inside the tower and jack it up through the top at the tower's concrete shaft at the 1500ft level. Three antenna designs were made and each rejected. In October 1973 (although stated as June 1973 by account of a March 22nd 1975 Toronto Star article), Wayne Baigent (CANRON’s engineering manager) chose to construct and hoist up a lattice (tubular design) antenna frame via a jib crane, piece by piece. While this was deemed a good and acceptable design, it would have resulted in an antenna core which could twist and bend more easily than a rigid steel structure. As fate would have it, the appropriate quantities of metal were not available to fabricate the tubular antenna design.

A young and new recruit, Jerry Morrow, who had been a University of Waterloo CoOp student with CANRON, and now recent full time hire (at age 23, 1974), came up with the alternative design of a rigid low-alloy steel core antenna for the CN Tower, fabricated as 39 metal "can" segments that would be hoisted up and stacked one upon each other. The question remaining was "How were the multi-ton 'can' segments to be hoisted up to the top of the tower, where winds can be quite blustery?". The Foundation Co. had suggested using large weather balloon (as used in logging), tethered to long guide lines to the ground - however, that idea was quickly rejected due to the length of such tethering cables, and the in-ability to attain sufficient precision for placing each segment.

At this time, as an avid reader of the Popular Mechanics magazine, Jerry Morrow had become aware of Erickson Air-Crane Inc. and their primary work of using Sikorsky S-64E helicopters to do logging in Oregon and Washington state. CANRON’s Stu Eccles approached Sikorsky and then the two civilian operators of S-64E's, Everygreen Helicopter of Oregon and Erickson Air-Crane of Marysville, Calfornia. CANRON asked both companies if they would consider taking on the job to remove the CN Tower's crane and make dozens of helicopter lifts to erect the tower's metal-core antenna. It was stated by CANRON that Erickson was reluctant to take on the job, as their main focus was logging and not construction related work. CANRON then approached Sikorsky themselves and sold them about the marketing potential that the CN Tower job would offer to their company and that of Erickson Air-Crane Inc. Tenders were put out to both companies and Erickson came in lower at a flat fee of US$230,000 (1975 dollars) for 36 working days, being used for a period of 22 days. Sikorsky then persuaded Erickson to take on the job, which they did, and to great success to their company and future reputation + marketing. At the time, in 1975, Erickson owned three S-64E helicopters, valued at US$4 million each (1975 dollars).

During the fabrication stages of the antenna cans at CANRON’s Disco Rd facility in Etobicoke, Ontario, it was unclear as to whether a helicopter would actually be used, as that was still not a guarantee during 1972 and 1973. Hence, the antenna mast was designed to be broken down into very basic pieces and re-assembled, piecemeal, by a jib boom crane through human manpower, which may have taken an estimated 6 months to complete vs. the 3-1/2 weeks by helicopter. This answers the basic question of “Why are the can segments bolted together rather than being fully welded?”. The round holes in each can were provided so that EMI of England could install the electronic components of the antenna later on in the year.

CANRON was awarded the Montgomery Memorial Medal for innovation in construction in Canada by the Canadian Construction Assoc. for their work in engineering and erecting the CN Tower’s metal core antenna.

-------------------

The antenna used two static “tuned dampers” to help reduce the sway and natural vibrations of the antenna mast. They were designed by several young Canadian engineers under the guidance of D.L. Allen, a University of Toronto professor, who headed up Vibron Ltd. It is based on the "hula hoop" principle for which the heavily lead-ladden 10 ton "hoops" hang free of the antenna and help to stabilize it. As the antenna hits the hoops, their dead weight helps to "nudge" the antenna back into position – they are allowed to move horizontally to a maximum of 2 feet. The lower damper acts as a pendulum while the upper damper as an inverted pendulum. The first damper was placed 135ft from the base of the antenna mast and the second 50ft higher. CANRON fabricated the 14ft diameter ring for the bottom unit and the 10ft diameter ring for the top unit.

Attachments

Last edited: