Written like an Architrivia article, but thought that sharing it as a discussion thread was more appropriate in this case. Feel free to adapt it as an article.

Back in the 1960s, the car was king and freeways were the way of the future for cities. Of course we don't see it that way anymore, but before we realized all of the downsides that car-focused design and neighbourhood-dividing freeways would have on our cities, many of them succumbed to the thinking of that era and carved themselves up to benefit the almighty car.

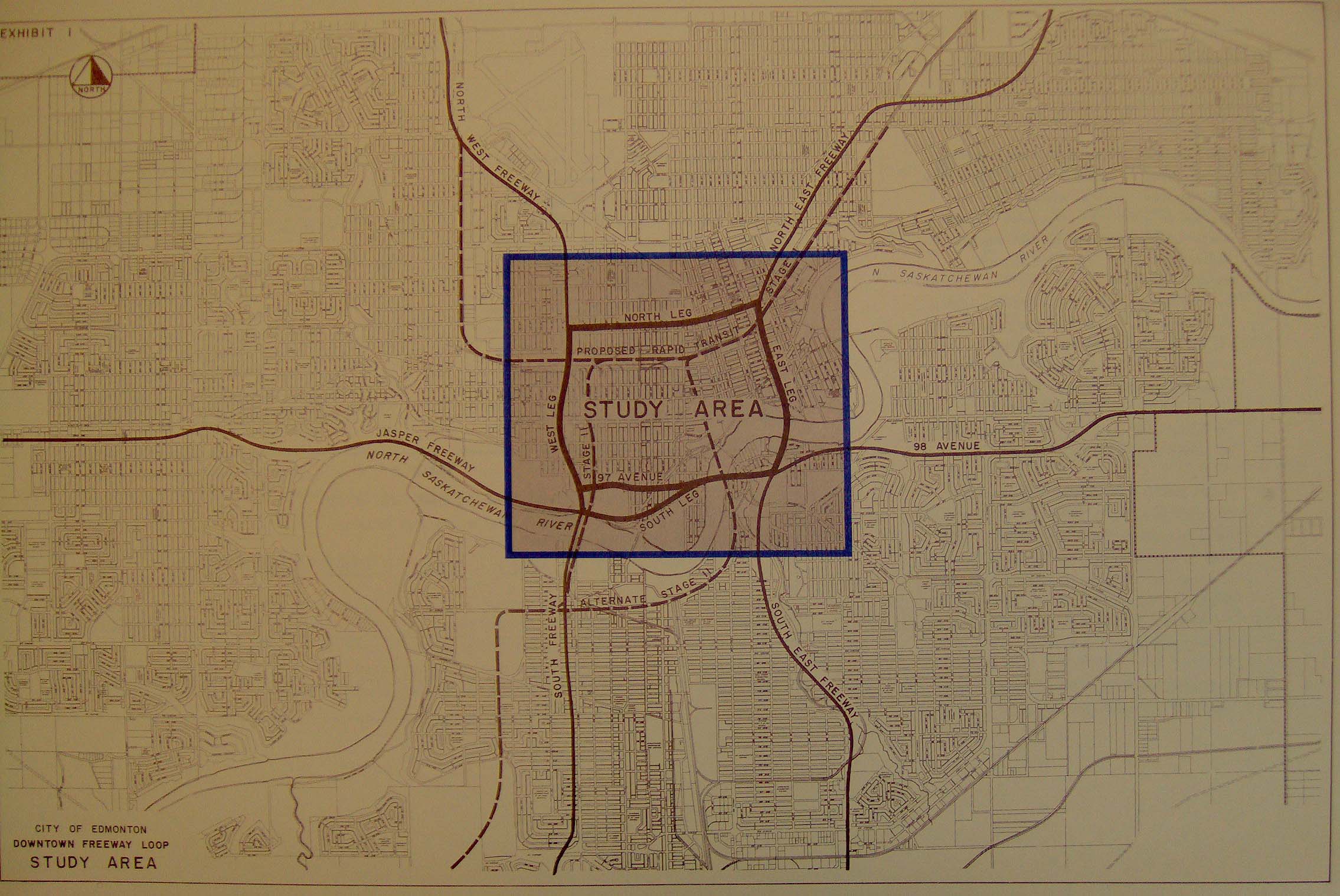

Some cities were lucky and dodged this bullet, but many of them still only narrowly. Edmonton was one such city; in 1969 it had commissioned the Metropolitan Edmonton Transportation Study (METS), which envisioned a freeway loop around the downtown core with connectors extending to all corners of the city.

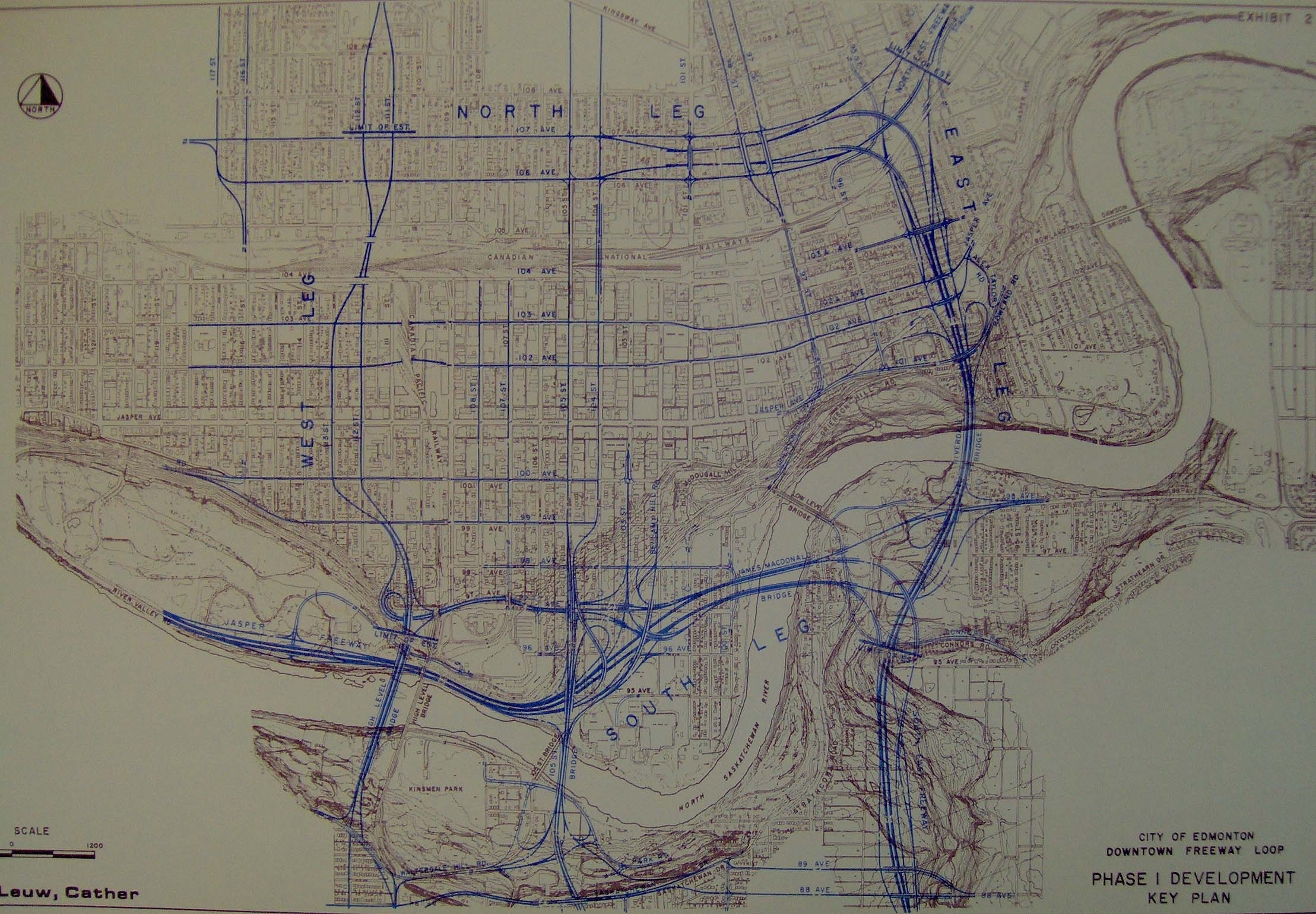

Detailed plans were made for the first stage, a north-south freeway cutting through the east side of downtown, connecting with a freeway to the west end of the city. The plan would have used the city's natural topography to its advantage, cutting the freeways through the river valley, and Mill Creek and MacKinnon ravines.

Stage 1 Ultimate Plan

Stage 1 itself was divided into six sub-stages of development. Only the first of these ever saw the light of day, in the form of the James MacDonald Bridge and the interchange just to its east (helping to explain the seemingly bizarre and overbuilt design to those who are unfamiliar with this history):

Stage 1 Sub-stage I, the only part of the plan that would be built

The plan saw huge opposition from residents in the neighbourhoods that were in the way of the roadways and interchanges, but it was really when the city decided to adopt and build an LRT line in anticipation of the 1978 Commonwealth Games that put METS to rest, signalling a shifting priority to more efficient transit systems over roadway construction and expansion.

Ultimate METS Plan - A bullet dodged

One cannot help but appreciate the audaciousness of METS; though certainly visionary, it was a vision for another era. Many cities that realized similar visions are still paying the costs of them - in infrastructure maintenance, unmanageable traffic, health and air quality problems, segregated neighbourhoods, downtowns with limited accessibility and overbuilt parking, and more.

In abandoning the plan, Edmonton not only saved itself from those same costly drawbacks, but saved some of its most interesting neighbourhoods and some of its most beautiful natural areas and ravines.

MacKinnon Ravine, where the western freeway would have been

Sources:

http://albertaroads.homestead.com/edmonton/plans/ - Go here for many more detailed images of the freeway plans

http://edmontonjournal.com/news/local-news/the-history-of-the-funding-of-edmontons-lrt

Back in the 1960s, the car was king and freeways were the way of the future for cities. Of course we don't see it that way anymore, but before we realized all of the downsides that car-focused design and neighbourhood-dividing freeways would have on our cities, many of them succumbed to the thinking of that era and carved themselves up to benefit the almighty car.

Some cities were lucky and dodged this bullet, but many of them still only narrowly. Edmonton was one such city; in 1969 it had commissioned the Metropolitan Edmonton Transportation Study (METS), which envisioned a freeway loop around the downtown core with connectors extending to all corners of the city.

Detailed plans were made for the first stage, a north-south freeway cutting through the east side of downtown, connecting with a freeway to the west end of the city. The plan would have used the city's natural topography to its advantage, cutting the freeways through the river valley, and Mill Creek and MacKinnon ravines.

Stage 1 Ultimate Plan

Stage 1 itself was divided into six sub-stages of development. Only the first of these ever saw the light of day, in the form of the James MacDonald Bridge and the interchange just to its east (helping to explain the seemingly bizarre and overbuilt design to those who are unfamiliar with this history):

Stage 1 Sub-stage I, the only part of the plan that would be built

The plan saw huge opposition from residents in the neighbourhoods that were in the way of the roadways and interchanges, but it was really when the city decided to adopt and build an LRT line in anticipation of the 1978 Commonwealth Games that put METS to rest, signalling a shifting priority to more efficient transit systems over roadway construction and expansion.

Ultimate METS Plan - A bullet dodged

One cannot help but appreciate the audaciousness of METS; though certainly visionary, it was a vision for another era. Many cities that realized similar visions are still paying the costs of them - in infrastructure maintenance, unmanageable traffic, health and air quality problems, segregated neighbourhoods, downtowns with limited accessibility and overbuilt parking, and more.

In abandoning the plan, Edmonton not only saved itself from those same costly drawbacks, but saved some of its most interesting neighbourhoods and some of its most beautiful natural areas and ravines.

MacKinnon Ravine, where the western freeway would have been

Sources:

http://albertaroads.homestead.com/edmonton/plans/ - Go here for many more detailed images of the freeway plans

http://edmontonjournal.com/news/local-news/the-history-of-the-funding-of-edmontons-lrt