Big number: $272 million, the estimated amount Toronto could raise each year by implementing a $4 per trip toll on the Gardiner and Don Valley Parkway. If Queen’s Park gave Toronto authority to issue tolls or taxes like this, city hall would be in a position to deal with budget pressures related to COVID-19.

In his quest to get Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Premier Doug Ford to pony up some cash to deal with the estimated $1.5 billion (or more) pandemic-related fiscal hole Toronto will be in at the end of the year, Mayor John Tory has been trying all kinds of strategies.

Some days he takes a stern approach, laying out

scenarios of doom if the city doesn’t receive funds — closure of subway lines and library branches, laid off firefighters, shuttered homeless shelters. Other days he plays the role of ego-soothing mediator, praising Ford while admonishing Trudeau, or vice versa.

On days when one of the governments has announced a bit of funding — like

last Thursday’s provincial announcement of $150 million in shelter and housing funds for Ontario municipalities — he’s like a patient dad lavishing encouragement on a child who has managed to put a sock on, describing it as a really great start toward finally getting dressed.

I won’t knock the mayor for any of this. He’s doing what he has to do in the face of a $1.5-billion problem. But let’s be real: it’s demeaning to see the leader of Canada’s largest city have to ask for money like this.

It doesn’t need to be this way. The provincial government could empower Toronto to solve this problem mostly by itself by making two changes to legislation.

The first move would be to permit Toronto to run operating budget deficits. Currently, unlike provincial and federal governments, Toronto is not allowed to pass a budget that is not balanced. If the government of Prince Edward Island, population 157,000, can be trusted to run deficits when times are tough, Toronto, with a population of almost 3 million, can probably handle it.

But don’t stop there. Allowing city hall to post deficits without the tools to increase revenue to pay down those deficits over time would just make the situation worse. Instead, the provincial legislature could pass an amendment to the City of Toronto Act expanding the kinds of taxes and fees Toronto is permitted to implement.

Don’t be restrictive. Give the city options and let Toronto council make choices.

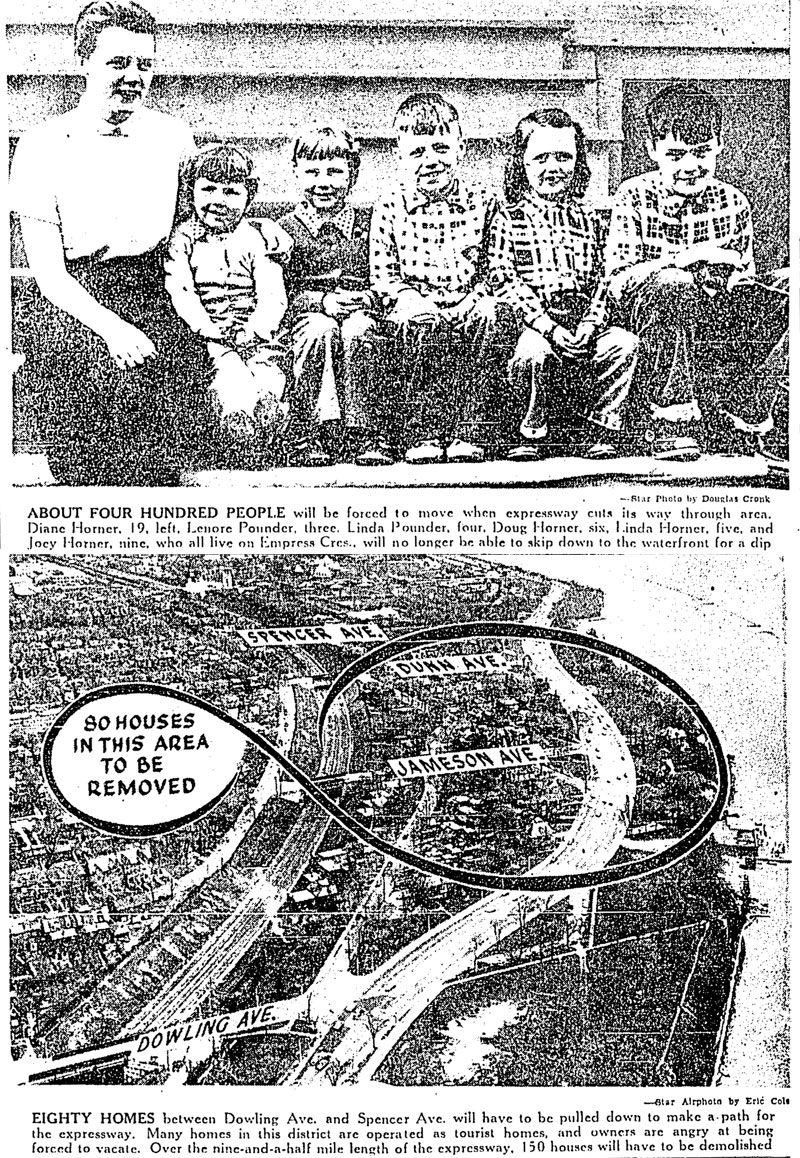

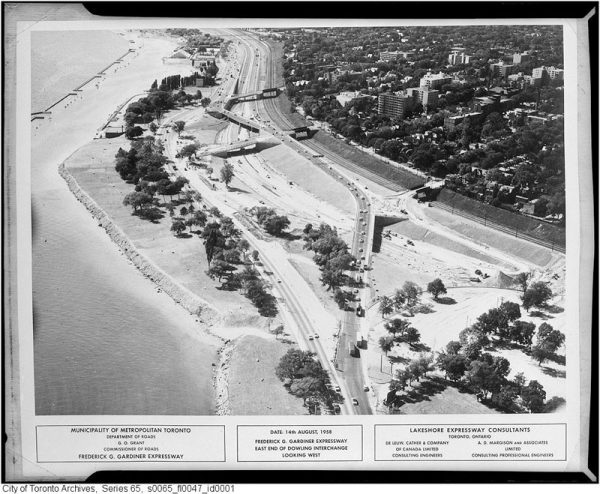

For example, council might choose to re-examine highway tolls. A toll on the Gardiner Expressway and Don Valley Parkway, something Tory

advanced in 2016 before he was blocked by then-premier Kathleen Wynne, could raise about $272 million a year if tolls were set at about four bucks a trip

according to estimates. That’s enough to pay down $1.5 billion of pandemic debt in about six years.

Or if tolls aren’t your thing, try something new — most cities of Toronto’s size aren’t as reliant on property taxes to pay for services. A

2016 study by KPMG looked at alternatives and found a Toronto sales tax of 1 per cent could raise a similar amount to highway tolls — about $261 million. A 1 per cent municipal income tax could raise between $580 million and $926 million, depending on implementation. A parking levy that taxes all parking spots in Toronto to the tune of $1.50 per day could raise about $535 million. Not too shabby.

There are downsides to any new tax or toll, of course. Implementation would need to be carefully balanced to make sure economic recovery from COVID-19 isn’t hindered.

But there are also upsides. Tolls or taxes that generate revenue that grows with the economy would motivate city hall to encourage economic activity. Local politicians would have a budgetary reason to push for events and policies that convince people to come to Toronto and spend money at local businesses.