U

urbanflight

Guest

When a new elevated highway was built in New Orleans in the 1960s, like other “urban renewal” projects in the U.S., it ripped through a predominantly Black neighborhood that had been thriving. Hundreds of homes were razed. Hundreds of businesses were lost. On Claiborne Avenue, the central boulevard in the neighborhood, hundreds of oak trees were torn out of a wide median that neighbors had used as a park. A coalition of community members now want to take the aging highway down—and it’s the type of project that the new administration could help make possible.

“There was a lot of disinvestment after buildings fell into disrepair. We lost a lot of historic building stock in terms of homes and commercial buildings,” says Amy Stelly, a designer and plannerwhose family has lived in the community for generations and who is now part of Claiborne Avenue Alliance, the group pushing to restore the former boulevard. “And it also changed the climate, because we now have cars instead of trees.” The now-missing park in the center of the avenue had mitigated the urban heat island, the effect that makes concrete-filled neighborhoods hotter on hot days. The greenery had also helped absorb rainwater in storms. As the new highway physically divided the area and destroyed the neighborhood’s economy, it also added pollution: People living nearby have a higher risk of asthma and other diseases.

Cities throughout the country are facing the same challenges—almost always in communities of color—and as roads wear out they now have the choice of repairing highways or completely transforming them. “There are many highways in the United States that are simply underutilized and therefore are ripe targets,” says Ben Crowther, who studies urban highway removal at the nonprofit Congress for New Urbanism. The nonprofit publishes biannual reports about which highways should come down first.

In Rochester, New York, for example, an “inner loop” highway had less traffic than a typical city street; the highway is now being removed, opening up land that can be used to build housing and new businesses. The city worked with the community living next to the highway to create a new vision for the area, and then gave developers requirements such as building affordable housing to help avoid forcing residents out of the neighborhood as property values increase. Crowther says that it’s critical for cities to have antidisplacement strategies in place before a highway comes down and a neighborhood suddenly becomes a desirable place to live again.

The federal government helped pay for the highways built through American cities in the middle of the 20th century. Now, federal policy could help transform those neighborhoods again, this time with a focus on equity and the environment. “Since it’s a product of the federal government, I think there’s also an imperative that the federal government takes a look at how we can repair some of the damage it could cause,” Crowther says.

The government should create a new competitive grant program to help cities and states deconstruct outdated urban highways and redesign neighborhoods, says a recent report from the nonprofits Third Way and Transportation for America. The report also recommends funding new land trusts that would help people living near former highways buy land, open small businesses, and preserve and develop affordable housing. “The land trust component of this was intentionally designed so that the communities that physically benefit don’t find themselves priced out of those benefits,” says Josh Freed, senior vice president for climate and energy at Third Way. The government can also fund new tools to help cities plan how traffic patterns will change; Freed says that it’s a misconception that taking down an elevated highway automatically adds traffic on surface streets.

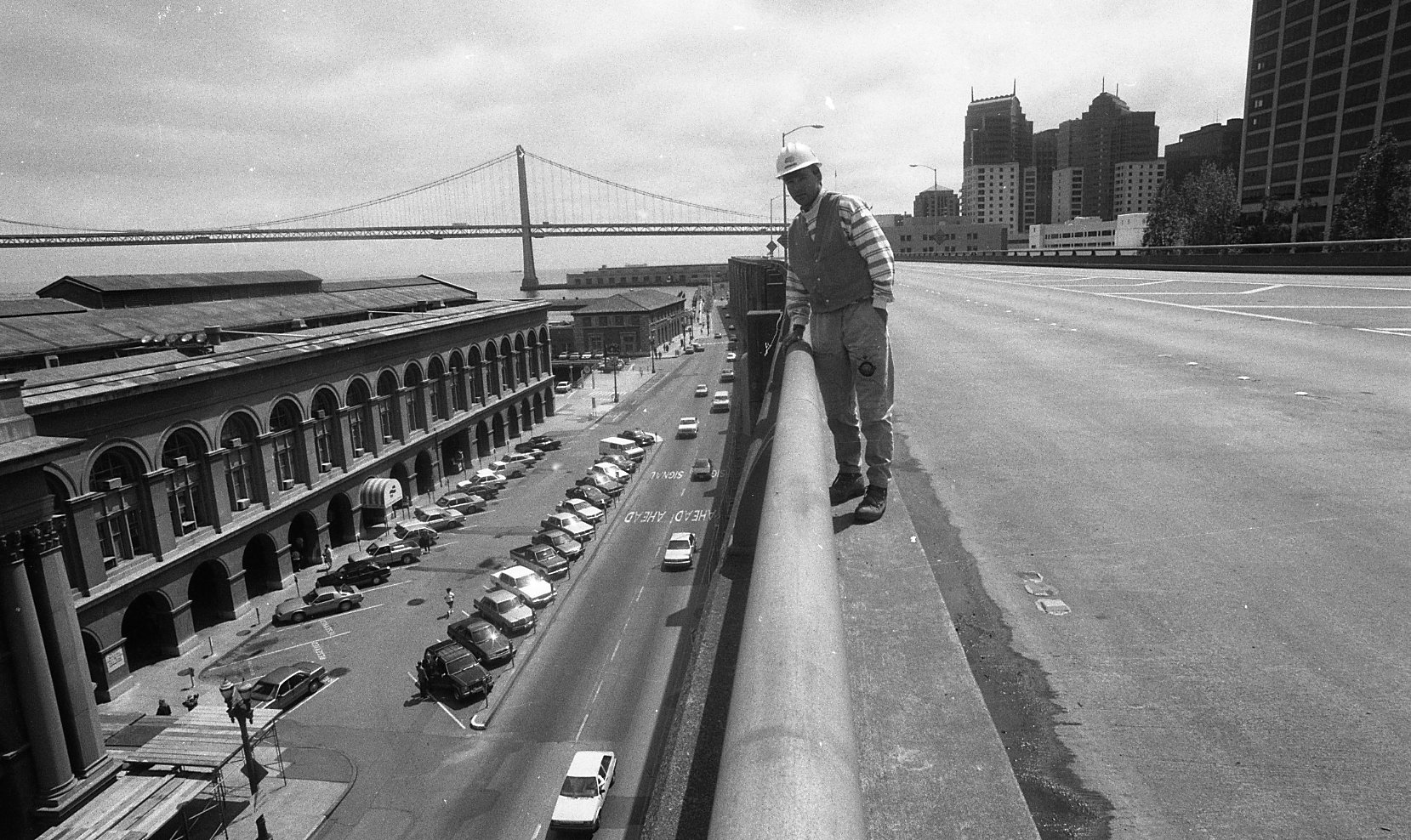

The Interstate Highway System was one of America's most revolutionary infrastructure projects. It also destroyed urban neighborhoods across the nation.

The 48,000 miles of interstate highway that would be paved across the country during the 1950s, '60s, and '70s were a godsend for many rural communities. But those highways also gutted many cities, with whole neighborhoods torn down or isolated by huge interchanges and wide ribbons of asphalt. Wealthier residents fled to the suburbs, using the highways to commute back in by car. That drained the cities' tax bases and hastened their decline.