Memph

Active Member

Yeah, I think it's very important to take into account how rail expansion projects fit in to the greater network.Back then, the ridership projections of Don Mills supported LRT, and it was logical given the ROW available.

It was only after Metrolinx released their Yonge North Relief Study that we learned both that Don Mills had subway level ridership potential, and that only Don Mills subway would provide relief to Yonge from the east.

In hindsight, it was pretty obvious how much bus ridership would be the intercepted via Relief Line North. Not sure why it took so long for that to become self-evident.

A few years ago, I looked on google maps to see what it recommended for the fastest transit route to Yonge & Bloor from various points in the east end of the city, to see which neighbourhoods fell into which routes catchment areas when it comes to Sheppard Subway vs Scarborough RT vs Danforth Subway.

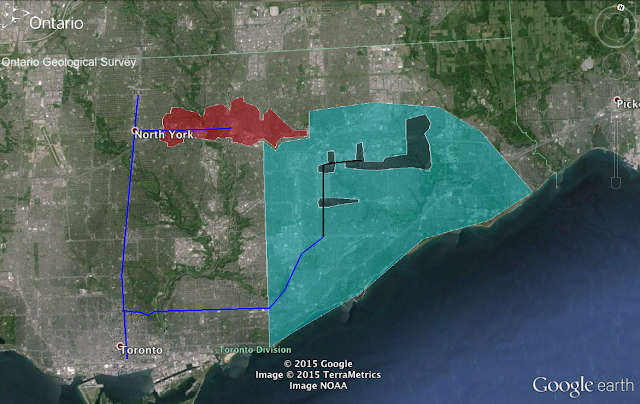

Since the Sheppard Subway and Scarborough RT are quite short, that means that if you take an intercepting bus route to transfer onto them, you'll have to transfer a second time onto the Yonge or Danforth Subway after just 1-2 stops, so it's not really worth it. Instead, google recommends that you take the bus directly to the Yonge or Danforth lines. It's only the people living within walking distance of the Sheppard Subway that are recommended to use it, hence the much smaller catchment area (in red) compared to the Danforth Subway (light blue).

With the Scarborough RT, it's even worse (in black). South of Ellesmere, even people within walking distance of the RT are often recommended to just take the Kennedy or Midland bus down to Kennedy Station. It's only further north that it makes sense to board the RT, once you can take it for more than 1-2 stops before transferring again. Buses along Brimley and McCowan also curve West to take riders directly to Kennedy or Warden Station. Scarborough Station doesn't just get twice as much ridership as the other RT stations combined because of the mall and condos, but also because it actually makes sense to take the RT if you live in those areas and in some parts of Malvern and Morningside too.

If you do the same experiment, but with the Financial District as the final destination rather than Bloor-Yonge, the catchment area of the Scarborough RT and Sheppard RT shrinks even further, as google recommends taking GO bus or GO rail lines.

A Scarborough extension probably could have drawn decent ridership from the Lawrence East buses however, thanks to the elimination of the transfer at Kennedy, and many bus routes would likely have been reconfigured a bit to feed into subway stations at Lawrence, or Ellesmere.

Similarly, the DRL would also intercept and redirect a tonne of transit users, to a significantly greater degree than even a Scarborough subway extension would have. Streetcar riders from East Toronto, subway riders from the Danforth line, buses from East York, the Eglinton East LRT, and even extending it to Sheppard would drawn a lot of riders as they would rather take the East-West routes to the DRL than N-S buses to the Danforth line or Yonge or Sheppard lines. I can easily see it getting 20k+ boardings at all stations. Past Sheppard you'd probably get significantly diminishing returns as those areas can be better served by upgrades in the GO rail and bus system when it comes to regional transit, and TTC buses should be able to handle the remaining local transit needs.