rbt

Senior Member

City signage will never be the same!

I predict city signage stays exactly the same; after 10 years of attempts to form a consensus on which font to use, all UT councillors retire.

City signage will never be the same!

I feel like it would take well over 4 years just to finally come to a consensus as to what to do with transit in Scarborough!10 years?

A UT slate will have just 4 years to get things done before the public vote us out in fury.

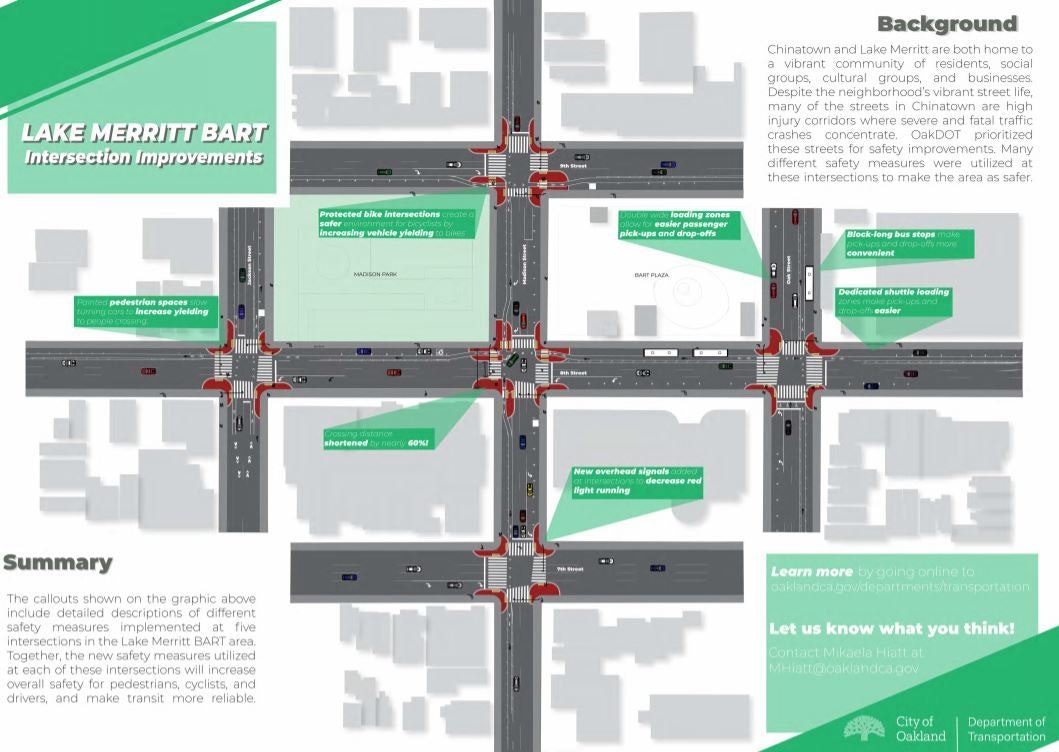

Background

Chinatown and Lake Merritt are both home to a vibrant community of residents, academic institutions, cultural groups, and businesses. Despite the neighborhood's vibrant street life, many of the streets in Chinatown are high injury corridors, where just 6% of Oakland Streets make up about 60% of severe and fatal traffic crashes. OakDOT prioritizes these streets for safety improvements to prevent future crashes.

OakDOT engaged BART, AC Transit, community groups and private companies to design innovative solutions to improve safety, transit access and overall mobility at five intersections around Lake Merritt BART station in Chinatown.

Summary of Improvements

The following is a list of safety measures that will increase overall safety for pedestrians, cyclists, and drives, and make transit more reliable:

- Painted pedestrian spaces will slow turning cars to increase yielding to people crossing

- Protected bike intersections create a safer environment for bicyclists by increasing vehicle yielding to bikes

- Crossing distance will be shortened by nearly 60%

- New overhead signals added to intersections will decrease red light running

- Double wide loading zones will allow for easier passenger pick-ups and drop-offs; the City is working with

rideshare companies such as UBER and Lyft to direct pick-ups and drop-offs to this location- Block-long bus stops will make pick-ups and drop-offs more convenient and efficient

- Dedicated on-street shuttle loading zones will make loading easier and faster

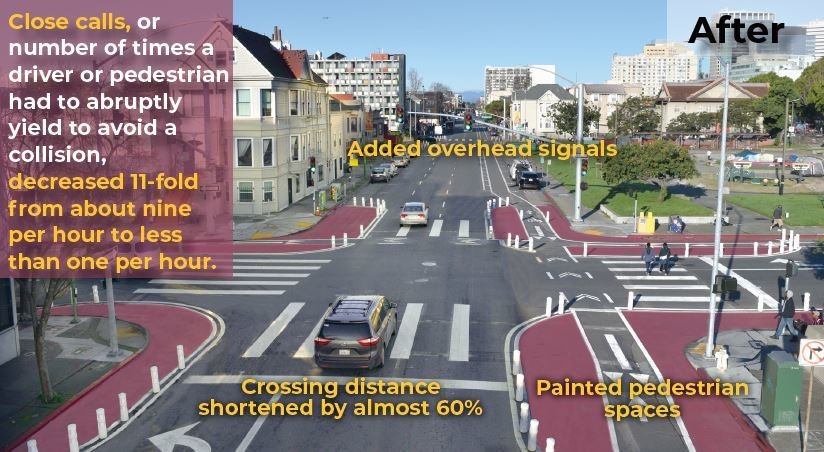

I suppose it doesn't work as well when/if some are already doing left turn onto curb lane?Interesting Study here on hardening the centre-line at left turn locations to improve safety.

It appears to show a very significant improvement.

Simple infrastructure changes make left turns safer for pedestrians

Centerline hardening can dramatically reduce close calls between vehicles and pedestrians.www.iihs.org

Before

View attachment 261392

After

View attachment 261393

A picture is also included in the link; but does not appear to me to fully match the diagram.

View attachment 261394

Lanes marked with that symbol have a speed limit of 30 km/h (about 19 mph). The default of 50 km/h (about 31 mph) is allowed in the other lanes. The marking with the oversized sharrow means:

- Bicyclists can use the lane;

- They have to ride in the middle of the lane.

All this started in 2013.

The city government was still reeling from the excesses of a real-estate bubble. Debt had ballooned to 7.4 billion euros after a failed Olympic bid. The city could not even dream of any significant infrastructure project. A giant fine from the European Commission was looming for the city’s failure to reduce its pollution levels.

City officials had to come up with something. This time they just couldn’t buy their way out of trouble. So they tried something different: a plan to increase cycling modal share without any large infrastructure projects.

The first plan was modest.

City officials started with a timid plan of “ciclocarriles 30” along the avenues and boulevards surrounding the Old Town. “Ciclocarriles 30” means 30 km/h bike lanes. The plan also included a municipal bike-share scheme that would use electric bikes, because Madrid is notoriously hilly.

In the beginning, nobody thought much of the plan.

In a chaotic and aggressive environment, motorists would not welcome the new users on “their” roads. Madrid city police have a well-deserved reputation for not enforcing traffic laws. Most people thought of the plan as some low-cost desperate measure to postpone the EU fine for a while, at least until a different administration was in charge. I’m not even sure that the city officials who created the plan had much faith in it.

Onward to Modelo Madrid.

Fast forward five or six years. Madrid city police still turned a blind eye to speeding, but the unexpected happened.

Madrid’s undisciplined, chaotic, aggressive motorists can be seen moving slowly behind a cyclist, waiting for the right moment to overtake — changing lanes to pass in the lane to the left.

The true benefit of the 30 km/h (19 mph) speed limit is not that motorists comply with it, but that they drive at 15 km/h (9 mph) behind cyclists without even revving their engines. A new generation of cyclists — many of whom started riding on the new municipal white electric bikes — uses these roads with confidence.

Every road user is mandated to control his or her traffic lane.

A third measure sustaining this change was a city ordinance issued in 2010, which not only allowed but made mandatory riding on the center of the lane.

In the video below, shot by the rider of a folding bicycle, nothing exciting happens, so don’t feel compelled to watch it all the way through.

We can now say that slow lanes were the origin of the so-called Modelo Madrid. The Madrid Model recognizes urban cycling as a transportation mode equal to any other, not requiring special infrastructure but granting the same rights to cyclists as to other vehicle operators.

No cyclists ride on the sidewalk. Cyclists grant the same respect to pedestrians as they demand from motorists. Modelo Madrid puts in practice many of the principles pioneered by John Forester and refined in the United States by CyclingSavvy.

Modelo Madrid: the way of the future?

As with any other aspect of public policy, we can’t “ride” on our laurels — to paraphrase the English idiom — and expect equal treatment for cyclists in Madrid forever.

Economic stimulus money spent on “sustainable” projects is always a threat for urban cyclists, especially in these COVID-19 times. Going back to the segregated model is still possible. Some very loud cycling activists and associations are always demanding narrow bike lanes in the door zone or on sidewalks, following the North European model.

Which way should US states (and Canadian provinces) go? Could there be slow lanes on multi-lane streets in the USA (and Canada)? Keep in mind that higher speeds are common now on e-bikes, which probably did not in exist when Seville bikeways were planned and constructed.

Consider that automated crash avoidance is becoming common on motor vehicles, and improving. A transition to autonomous vehicles will follow, in time.

Suppose that a hoped-for decrease in motor traffic occurs with autonomous vehicles. Consider also the dangers of edge riding, and the reduction in efficiency and safety when turning vehicles must cross the path of through-traveling ones, rather than merging before turning.

All of these factors suggest that an integrated model like the Modelo Madrid could become more compelling as time passes.

Does US practice support the Modelo Madrid?

There is no specific mention in the model US traffic law [8] of different lanes with different posted speed limits. Yet these are in wide use, established indirectly.

In several states, large trucks are held to a lower speed limit than other vehicles [9], and are prohibited from using the leftmost lanes on multi-lane highways. Edge-of-the road “friction” with parked vehicles, walk-outs, drive-outs and parking decreases the safe speed in the rightmost lane on city streets.

The general rule is to pass on the left, in the “fast lane”. But faster vehicles may pass bicyclists on the right in a right-turn lane, and sometimes a bus lane.

In all of these cases, the basic speed limit applies: to drive no faster than is reasonable and prudent. That speed is established by the design of the street and by the users who are present. Here’s an example of a bike lane to the left of a bus lane on University Avenue, Madison, Wisconsin.