Mr. Apostolopoulos himself donated $1,220 to Mr. Ford’s campaign in his riding of Etobicoke-Lakeshore in 2018. In 2019, he gave $1,083 to the Progressive Conservative Party in 2019 and $944 to the PC riding association in Leeds-Grenville-Thousand Islands and Rideau Lakes, Mr. Clark’s riding.

The records also show PC donations from his son, Steve, who is the managing partner of Triple Properties – and previously a massive Liberal donor. Since 2018, he has given $4,446 to the PCs, including $1,222 to Treasury Board President Peter Bethlenfalvy, who is the MPP for Pickering-Uxbridge.

No one from the Triple Group would agree to an interview. In an e-mailed statement, the company’s head of special projects, David White, dismissed the notion that donations had anything to do with the MZO.

“The attempt to link the MZO to political donations is entirely wrong, and the matter of donations has never been raised in any conversations we’ve had with local politicians or the provincial government, whether the Liberals or PCs were in power,” Mr. White wrote.

In an e-mail, Adam Wilson, a spokesman for Mr. Clark, dismissed as “nonsense” the idea the donations played any role in the government’s decision, noting the developers’ previous support for the Liberals and saying the request for the MZO came from the local municipality and Durham Region.

Speaking to reporters last week, Mr. Clark said the government was now seeking public comments on its future use of MZOs. He also repeated that, except for projects on provincially owned land, each MZO has come at the request of a local council.

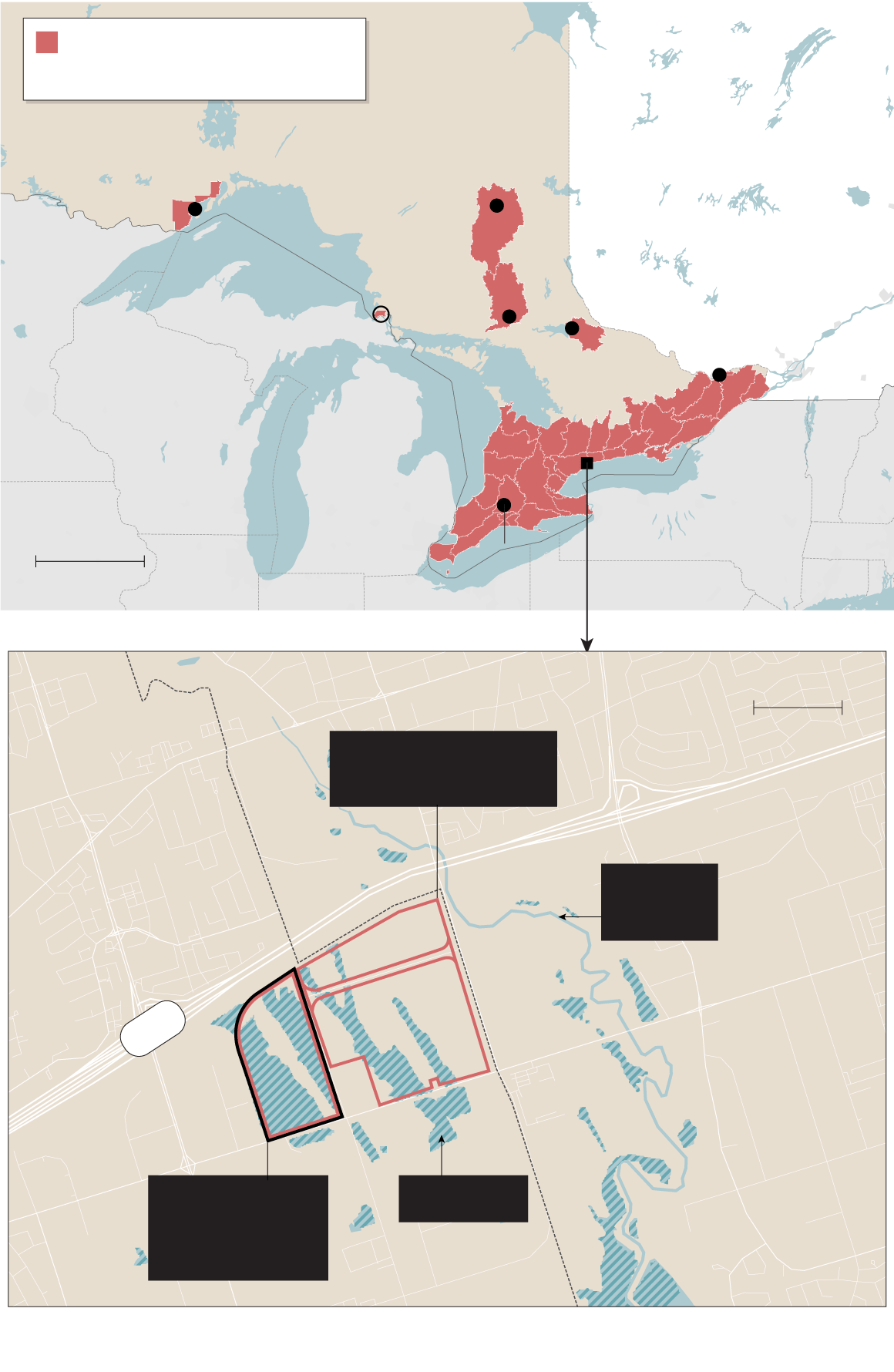

In Pickering, the city asked for its MZO after a unanimous council vote in May. However, as they made that decision, councillors had before them only a presentation from a lawyer for the developer and a letter from a consultant acting for the developer. The council minutes, which say traffic concerns were raised, are silent on the topic of the environment.

Pickering Mayor Dave Ryan defends the MZO, saying his city is desperate for the thousands of jobs a large distribution centre would bring as it recovers from the economic effects of COVID-19. He also said the MZO was not a “blank cheque,” as the developer must still engage in talks with the TRCA about replacing the wetlands.

Asked why the new warehouse must go in a protected wetland, and not on any number of other nearby potentially suitable sites, the mayor said: “The site’s owned by a private developer. They’ve got their business relationships. They brought forward a proposal that we felt was beneficial overall for the municipality.”

Mr. Ryan also denied that his acceptance of $4,800 in donations from Mr. Apostolopoulos and his family – out of $73,750 raised for his 2018 election campaign – played any role in his decision.

A key question in the Duffins Creek affair that remains is whether the state of the wetlands still warrants their protected status.

A section of the City of Pickering’s website devoted to promoting the MZO cites a summary of an unnamed environmental report concluding the wetland is in decline. But that report, commissioned by the developer, was never submitted to the city. The province, the developer and the TRCA declined to provide the report to The Globe and Mail. The TRCA did say that the report in question was not a comprehensive study of the impacts of paving the wetland, and that no such study had yet been done.

According to a copy obtained by The Globe, the report, by consultants with Beacon Environmental, does say the area “may provide stormwater volume control functions (e.g. flood attenuation, storage, etc.).” However, the wetlands, increasingly surrounded by industrial properties, “generally provide limited ecological functions for flora, fish and wildlife,” although “locally rare flora and a rare vegetation community are present.”

The report does not conclude whether the provincially significant wetland designation should be lifted, and says more study is needed. But it says that “without intervention the functional importance of the wetlands will likely continue to decline over time.”

Duffins Creek itself winds its way to Lake Ontario just over the border in neighbouring Ajax, Ont., where Mayor Shaun Collier has been campaigning against the warehouse, and raising traffic concerns about the Durham Live project as whole.

Mr. Collier, who also acknowledges taking campaign funds from the Apostolopoulos family, says stripping this plot of its protected wetland status will raise its value from virtually worthless to as much as $1-million an acre.

“You have to wonder why they would convert a provincially significant wetland when there are ample other areas to build this project within a kilometre,” Mr. Collier said. “... That warehouse could go anywhere. We have hundreds of acres available.”

Mr. Clark’s office says the environmental concerns over the proposal will be addressed through negotiations now under way between the TRCA and the developer. Even with their weakened powers, conservation authorities can still seek to attach conditions to development approvals, such as insisting on flood-prevention measures or the replacement of destroyed wetlands.

However, under Ontario’s recent changes, a developer could appeal these conditions to the province’s minister of natural resources and forestry or to the province’s land-use tribunal.

Jennifer Innis, the chairwoman of the board of directors of the TRCA, said that until the surprise legislative changes earlier this month, the TRCA could not have legally issued a permit for development in a provincially significant wetland. (That status can normally only be lifted by the province’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, which is now undertaking a review in this case.) Now, she says, being forced to issue this kind of permit in the face of flood dangers or other environmental problems could see her board face legal liability.

For just this warehouse in Pickering, Ms. Innis said TRCA could impose $40-million to $60-million in costs on the developer in exchange for the destruction of the wetlands, including the price of creating new ones somewhere else.

According to a memorandum of understanding signed between Triple Properties and the TRCA, and obtained by The Globe, the developer has agreed to a 1:1 replacement ratio for wetlands that are destroyed.

But Tim Gray, executive director of Environmental Defence, warns that replacing wetlands is not the same as preserving existing ones that have taken thousands of years to form.

The development industry supports the reining in of conservation authorities, and the use of MZOs to get projects moving.

Developers have long complained about approvals that get stalled for years by conservation authorities that they accuse of often overstepping their mandates. Joe Vaccaro, CEO of the Ontario Home Builders’ Association, said the new rules would give developers more clarity when they are seeking permission to build something. But he said conservation authorities would still be able to address environmental and flood-protection issues.

“The idea that someone’s just going to start building in floodplains – it’s impossible,” Mr. Vaccaro said. “That’s not how it works.”

We also have the great calamities of COVID-19, Donald Trump, and Doug Ford, all at the same time as the winter solstice.

We also have the great calamities of COVID-19, Donald Trump, and Doug Ford, all at the same time as the winter solstice.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/COO4TCRDTJHQ3MOA7CP6HMXZWI.jpg)