darwink

Senior Member

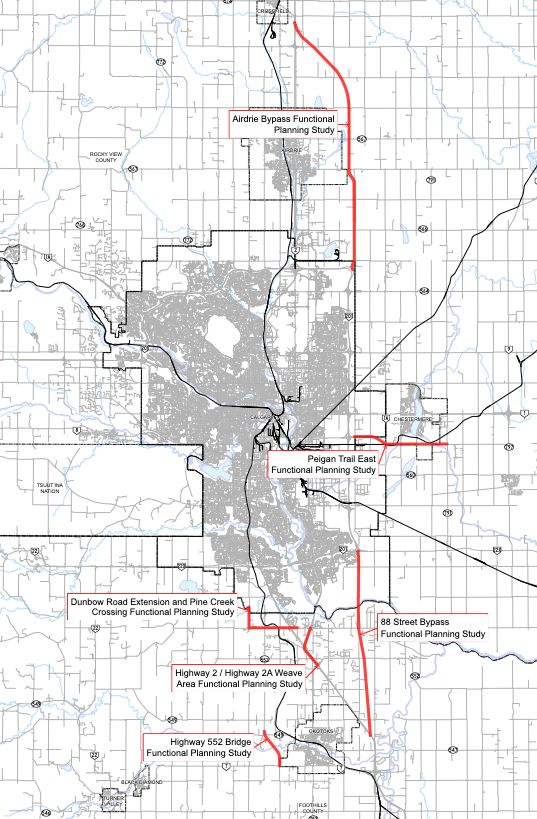

Aside: We're (eventually) getting bypass roads!

Memorial is one of those "Calgary-special" roads where it's a lot of different types of road all along it. Makes it tricky to talk about in it's entirety, given it's role/design dramatically changes based on local context.I'm curious how Memorial will work when it gets to Chestermere, will it just die at Rainbow Road?

Preferred design has it crossing the tracks at-grade. I assume the CN line there just doesn't see enough traffic to justify more overpassI suppose it also has to go over the tracks.

Wow the TUC is ginormous. In a unintentional way, it's practically a greenbelt - it's so wide there's got to be millions of additional costs just to cross it with any utilities and bridges. I wouldn't be surprised if development was ironically slowed down from the creation of the TUC/ring road , at least until those first servicing connections were made across it.The right-of-way reserved in the Transportation Utility Corridor for this flyover is still pretty substantial. The TUC is the grey in this map:

View attachment 558935

Most cities would kill to have an easy right of way for roads and utility lines. That being said, it could have been narrower.Wow the TUC is ginormous. In a unintentional way, it's practically a greenbelt - it's so wide there's got to be millions of additional costs just to cross it with any utilities and bridges. I wouldn't be surprised if development was ironically slowed down from the creation of the TUC/ring road , at least until those first servicing connections were made across it.

Provisioning for pipelines and electricity at 1980s standards made the width make sense.Most cities would kill to have an easy right of way for roads and utility lines. That being said, it could have been narrower.

Most cities would kill to have an easy right of way for roads and utility lines. That being said, it could have been narrower.

That makes sense to me as the rationale. The best example of something similar I can think of is Toronto's Highway 407 corridor, clearly designed with some the same pressures and thinking (e.g. "this time we really want to be sure we keep enough land!").Provisioning for pipelines and electricity at 1980s standards made the width make sense.

I think there's a huge opportunity in Calgary if we can ever figure out how to make our medium and larger roads not as shitty to live near. Calgary's road hierarchy is a bit bizarre in that we have a disproportionate amount of these mid-tier roads cutting through communities or on their boundaries - they aren't highways or major corridors, but are also larger than just your local roads. Memorial east of 36th Street NE is a good example, but this category captures a ton of weird boulevards and minor arterial streets all over ranging from 2 lane collectors up to wide 4-lane with a median 1970s-era boulevards.I hate how people move next to a future road then try to protest the road going in. It's 100% going to happen, deal with it lady! lol

Cool !Aside: We're (eventually) getting bypass roads!

View attachment 558901